By Ruth Keah and Salome Kitomari

Kenya, Tanzania: At Kibuyuni, a coastal village in Kwale County, Kenya, Fatuma Mohammed (50), a mother of two, rises as the first rays of the sun gently kiss the horizon. Donning her traditional kanga, a colorful wrap around her waist, and another one on her head to cover her hair, Fatuma begins her journey to the shore.

She wears recycled tire sandals to protect herself from any sharp or foreign objects in the ocean and wades about 500 metres away from the beach through knee-deep water to reach her carefully cultivated seaweed beds.

With deft hands, Fatuma tends to her seaweed crop three days a week. She cautiously selects the healthiest and most vibrant seaweed shoots, expertly pruning and nurturing them to ensure optimal growth.

Seaweed farming, also known as seaweed aquaculture or mariculture, is the cultivation and harvesting of various species of marine algae for commercial purposes. It involves the deliberate cultivation of seaweed in controlled environments, such as coastal areas or designated seaweed farms.

As an ingredient, it is prized around the world for its many benefits, which include being a source of protein and vitamins, lowering blood sugar levels, reducing heart disease risk and controlling cancer risks.

Globally, China is the world’s biggest producer of seaweed, accounting for 57 % of global volume But over the past decade, global seaweed production has increased with an estimated value of $59 billion in 2019. A recent report by the World Bank identified ten global seaweed markets with the potential to grow by an additional USD 11.8 billion by 2030, as interest in seaweed as a food source, carbon sink option, and renewable product from consumers, farmers, researchers, and business leaders blossoms.

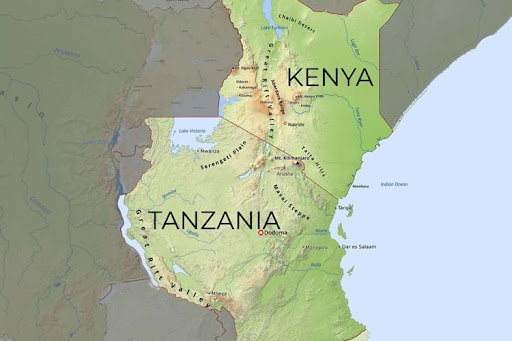

Interest in seaweed is certainly growing along the coasts of Kenya and Tanzania.

Following research trials and support from various sectors including Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), the harvest doubled from 5,204 kg in 2012 bringing an income of KES 46,840.5 (USD $426) to 10,554 kg in 2018 at the cost of up to KES 263,850 (USD $2,398).

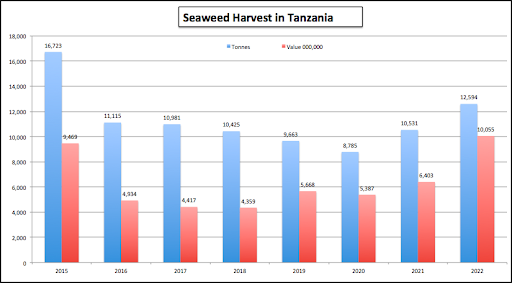

Similarly in Tanzania, according to the Ministry of Blue Economy and Fisheries, productivity of seaweed increased from 16,723 kg (Tsh 9,469,000,000) by 2015 to 12,594 kg (Tsh 10,055,000,000) by 2022.

In Tanzania, according to the Zanzibar State of Economic Report 2021, there were 12, 611 kg of seaweed worth Sh. 11.9 billion exported in 2021. This was an increase of 9.7 % compared to the previous year.

Fatuma, who learned about seaweed farming from the Kenya Marine Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), which has been researching seaweed farming, was lucky to be one of the first to participate in a pilot project. After learning from a women’s group in Tanzania, she founded the Kibuyuni Seaweed-Self-Help Group in Shimoni, Kwale County in 2010.

The group started with 113 members with the majority (75%) being women. Now, it boasts 240 members who practice seaweed farming in six block farms, each with a capacity of 300 seaweed planting ropes. The farmers grow two species of seaweed, spinosum and cottoni, harvested in around 30-45 days.

In a village where the predominant economic activity of fishing is mostly reserved for men, the group sees seaweed farming as a sustainable economic opportunity that weans them away from over-reliance on their male counterparts and enables them to contribute significantly to the family income.

Following research trials and support from various sectors including Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), seaweed farming is now earning Kibuyuni Village over USD 11,000 from the initial USD 2,000 in 2012.

Before turning to seaweed, the women used to rely on farming maize, beans, and peas. However, according to the National Drought Management Authority, Kwale was among the counties in Kenya that recorded below-average crop production driven by poor rainfall performance. Hence, the women could not get enough yield to sustain their family needs.

“You see, it was a taboo for women to go to the ocean and fish, hence we relied on dry land farming. However, poor rainfall and the destructive behavior of monkeys led us to explore alternative options,” Fatuma said.

With seaweed farming, they don’t need to rely on freshwater or chemicals like fertilizers and harmful pesticides to eke out a living from the land. As Fatuma pointed out, “Seaweed also grows at a much faster rate than trees, expanding by up to two feet a day.”

Economic resilience

“Most women here have embraced seaweed farming. To them, it is a savior who has come to rescue them from hard economic times. I am now able to pay school fees for my children because if you depend on the Ksh 2,000 or 3,000 (USD 14-22) bursary from the government, your children will not go to school, but when I go to the ocean and after 45 days I have Ksh 30,000-40,000(USD 215-287)–will my child go to school or not?” she asked.

Rehema Hassan, a mother of two, is a member of the Mwazaro Beach Management Unit (BMU) Self-Help Group, in a village that neighbors Kibuyuni. Their 168 members learned the practice from Fatuma’s group. She says for her, seaweed farming is a permanent job since the ocean never gets dry and she can do the farming all year round.

“The ocean doesn’t disappoint in terms of farming, you can plant seaweed more than six seasons in a year, it takes only two to three hours to plant the seaweed in your block, and is harvested in 45 days. It needs minimal supervision,” she said.

Rehema says they could not make ends meet relying only on her husband’s income from fishing. Climate change and human activities have led to a decline in fish populations in the ocean. He can barely get 10 kg of fish per day. According to a report by the Marine Stewardship Council, climate change threatens fish stocks. Areas in the tropics, like Kenya and Tanzania, are predicted to see declines of up to 40% in potential seafood catch by 2050.

Seaweed farming has also created job opportunities for youth at Kibuyuni.

“Seaweed farming has uplifted my life. I am now paying school fees for my siblings without struggling, I have also built a permanent house for myself and hopefully this year I will get married,” said Bakari Usi, a youth in his late 20s from Kibuyuni Village, who used to be a Bodaboda rider.

With four other youths, he produces shower gel, hair food, bar soaps, salt, baking ingredients, and other items from the seaweed, which they sell for Ksh100 (USD 0.717) per item.

“Seeing the success stories of women in Kibuyuni inspired me to invest my time and resources into seaweed farming. It’s not just about the financial gains, although that’s promising. It’s about contributing to the sustainable development of our region. With increasing demand for seaweed products in international markets, I see a future where our coastal livelihoods are transformed, and our communities thrive,” he said.

Carbon sequestration

Besides the impetus it has provided to women’s and youths’ livelihoods, the practice affords several benefits and protection to the fragile coastal ecosystem too.

According to a Frontiers report titled “Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Mitigation and Adaptation”, and various studies, seaweed helps mitigate climate change.

Seaweed plays a significant role in fighting climate change by absorbing carbon emissions, regenerating marine ecosystems, creating biofuel and renewable plastics, as well as generating marine protein. While forests have long been considered the best natural defense in the battle against climate change, researchers have found that seaweed is in fact the most effective natural way of absorbing carbon emissions from the atmosphere.

Bernard Fulanda, an associate professor in marine science and a climate change expert from Pwani University based in Kilifi County on the Kenyan Coast, says apart from seaweed creating job opportunities and empowering women economically, it also makes the ocean become resilient to climate change. He says if seaweed grows rapidly, it can capture substantial amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Professor Fulanda added that seaweeds have the ability to absorb excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, from the water, helping to mitigate water pollution and its associated environmental impacts.

“Seaweeds are forests of the ocean. If seaweed is done well and on a large scale, it can absorb CO2 in the ocean very well,” he said.

According to Professor Fulanda, recent studies suggest that globally wild seaweeds could sequester between 61 and 268 megatonnes of carbon per year, with an average of 173 megatonnes.

Fish Production

According to Omar Juma Suleiman, head of the Department of Marine Conservation in Mkondo, seaweed has significant environmental benefits, which is why there is a growing push to support its large-scale production.

He said; “Seaweed aids in the conservation of the marine environment and aids in fish production.”

Bakari Usi, the youth from Kibuyuni, says he has noticed that seaweed farming created a good breeding ground for fish compared to other areas in Shimoni, an observation that is also supported by the International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies.

Fatuma too, added that seaweed farming has also created safe and healthy breeding grounds for fish which are later harvested commercially or improve wild population levels. “The places where we do seaweed farming normally attract a lot of fish and this helps fishermen because they don’t go to the deep sea to catch fish hence it also protects the sea floor. This also contributes in one way or another to conserving the ocean ecosystem,” she said.

Coastal Resilience

African countries, including Kenya and Tanzania, are facing the imminent threat of losing their coastal heritage sites due to erosion and rising sea levels. Therefore, there is an urgent need for these nations to embrace seaweed farming as a sustainable solution.

Importantly, according to research mentioned in National Geographic done by Frontiers in a story titled ‘Seaweed ‘forests’ can help fight climate change’ aquaculture for climate change adaptation can also help with coastal protection.

According to the Marine Conservation Society, seaweeds, particularly kelp, can also help prevent coastal erosion by lessening the impact of waves. Because of their large size and dense structure, kelp forests can tolerate strong waves and currents, and buffer them. This helps protect the coast from erosion, which is primarily caused by strong waves.

“By creating coastal habitats, seaweed aquaculture can potentially contribute to some of the ecosystem’s functions that naturally help forests and macroalgal bed supports. For example, the canopies of farmed seaweeds, like those of wild seaweeds, dampen wave energy and hence, serve as live coastal protection structures buffering against coastal erosion,” reads the report.

Challenges

However, despite its obvious benefits, seaweed farming is not without its challenges. Although the farming of seaweed is proven to curb climate change, it is not immune to its impacts.

According to Bakari, seaweed can sometimes experience bleaching due to high temperatures. Bleaching occurs when the seaweed loses its color and vitality, turning white or pale. This phenomenon is primarily caused by the stress imposed on the seaweed’s photosynthetic apparatus when exposed to elevated water temperatures.

Fatuma Omari, 50, a seaweed farmer in Tumbe, North Pemba, noted another challenge: some women seaweed farmers who used to rely on shallow seashores have been forced to go further into the ocean due to the effects of climate change.

According to the Director of the Fisheries and Seafood Development Department, Ministry of Blue Economy and Fisheries, Zanzibar, Dr. Salum Soud Hamed, the cause has been identified as an increase in sea temperature.

“The rise in sea temperature has resulted in a decrease in harvest and the destruction of some harvests. Climate change has also made it impossible for seaweed to germinate in areas of the sea with low water levels, forcing farmers to relocate to areas with higher water levels, which also have access issues,” he said.

Adding “The women lack boats which can help them during harvesting to carry the seaweed from the ocean to the shores.”

40-year old Mariyam Said, from Pemba, Zanzibar added “Since we do not have a boat to help us get to the high water level, we are forced to depend on fishermen to transport us. We also need swimming lessons so that we can improve our swimming prowess which will help us save our lives whenever an emergency arises,” she says.

She also pointed out their lack of reflector jackets and other water protective gear to protect them from the sea. According to her, buying this equipment requires TSh. 6, 500, 000 (USD 2,701).

The Tanzanian Ministry of Blue Economy and Fisheries is working to build the capacity of seaweed farmers to better understand where to conduct their activities safely.

Mariyam also noted that the current market price is not worth their efforts. She calls on the government and seaweed buyers to consider paying them better.

Bosco Kimambo, who is working with Seaweed Cooperation Company in Zanzibar, which deals with buying seaweed from farmers, says farmers do not negotiate for the price. “Price depends on transportation cost, tax, and investment cost incurred by farmers among other factors,” he said.

“We lack technology to dry out our seaweed and so we are forced to dry them on the ground which reduces their value while some get destroyed especially during the rainy season, ” Fatuma laments.

And also we don’t have a reliable market to sell our value-added products,” Fatuma added.

Demand For Seewood Boosting The Blue Economy

Despite the challenges they are facing, coastal communities are embracing seaweed farming. According to Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), the unit price of seaweed has fluctuated widely from KES 9 per kg in 2012, to KES 30 per kg in 2023 for a total of KES 1,277,490 (USD $11,608) earned by the community.

However, there are promising projections for an increase in production. This growth is expected due to the government’s initiative to enhance production through the intervention of the Blue Economy Implementation Standing Committee. In the current scenario, farmers primarily sell their produce to middlemen, many of whom are located in Zanzibar. These middlemen subsequently sell the products to exporting companies.

In Tanzania, according to the Zanzibar State of Economic Report 2021, there were 12, 611 tons of seaweed worth Sh. 11.9 billion exported in 2021. This was an increase of 9.7 % compared to the previous year. Given this growing demand, scientists and policymakers seem eager to support the practice too–and help meet the needs of women seaweed farmers.

The Kwale county Governor, Fatuma Achani, said they will intensify seaweed production in the area by offering farmers capacity-building training and providing them with planting materials.

Researchers have begun implementing a model that allows locals, mainly women, to grow seaweed and rear fish in a controlled set-up along the Indian Ocean shores. This means women will no longer rely on men to bring them fish from the ocean; they will have their own production units – with both seaweed and fish – within the safety of the ocean shores.

Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) technology, being piloted in Kwale and Kilifi counties in Kenya, is under the umbrella of the Blue Empowerment project, funded by the International Centre for Research and Development.

It is being implemented by scientists from Kenya Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kenya Industrial Research Development Institute (KIRDI), the African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS), and Kenyatta University. It aims to address socio-economic barriers preventing women from accessing and exploiting marine resources in Kenya’s coastal region through the adoption of climate-smart integrated multi-trophic aquaculture of seaweeds and fish for improved livelihoods and resilience

The project aims to give women more power and control of Kenya’s lucrative Indian Ocean share of the 142,400 km2 Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The IMTA technology involves building special cages along pre-identified areas of the ocean which will allow women to cultivate seaweed and rear fish in the same system.

Dr. Linus Kosambo, a research scientist at the Kenya Industrial Development Institute (KIRDI), believes the innovation will allow women in the region to exploit the lucrative blue economy without necessarily going deep into the sea.

“IMTA has the potential to enhance the exploitation of Kenya’s vast marine resources and contribute significantly to the blue economy by opening new avenues and opportunities for aquaculture. The breeding areas of fish have been changing and their movement has become much more unpredictable due to climate change. IMTA comes in to partly solve this problem by making the production systems more dependable, predictable, and resilient to climate change,” he said.

The blue economy refers to the sustainable use and management of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ocean ecosystem health. It encompasses a wide range of economic activities and sectors that are directly or indirectly linked to the oceans, including fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, shipping, marine renewable energy, coastal management, and marine biotechnology.

“As a resilient, low-carbon and environmentally friendly innovation, IMTA will not only enhance and diversify income streams amongst women in the region but will also help mitigate effects of climate change and Covid-19 by creating alternative job opportunities,” he concluded.

In Zanzibar, too, support has been growing. Current President Dr. Hussein Mwinyi Hussein says the government will provide full support to increase production.

Seaweed farming officer from the Blue Economy Ministry, Asha Khamis Sultan says that Tanzania has already given seaweed farmers 500 boats through the COVID-19 relief fund.

She says that this effort by the government through Zanzibar State Trading Corporation (ZSTC) aims to help seaweed farmers to access high water level points to increase their harvests. She further notes that the government through the trade ministry is already buying seaweed at different prices depending on the value and quality.

“We are also creating awareness with the seaweed farmers on how they can increase their quality for better market price, by accessing the high water areas where they will get a bumper harvest,” she says.

Way Foward

With renewed determination, Fatuma Mohammed and her fellow farmers have embraced seaweed farming for the foreseeable future. With state support, they envision a time when seaweed farming will not only thrive but also serve as a beacon of hope for coastal communities in Kenya and Tanzania.

“Seaweed farming has empowered us to reclaim our voices and shape our own destinies. As we look to the future, we believe that strengthening our knowledge, embracing sustainable practices, and expanding market opportunities are the way forward. Together, we will continue to cultivate resilience, protect our marine ecosystems, and create a brighter future for ourselves, our communities, and the seaweed farming industry as a whole,” she concluded.

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.