By Helen Clark and Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

We have the means to make pregnancy and childbirth safe – so why so many needless deaths?

The death of Zainab from bleeding after giving birth to her daughter, Safiya, in Yemen highlights how rapidly complications can escalate around childbirth and the tragic impacts that can follow, especially in fragile states. In Zainab’s case, the hospital where she planned to give birth lost its gynecologist because of funding shortages, and she was forced to deliver at home without the help she needed.

While each woman’s story is unique, data show that such tragic outcomes occur all too frequently around the world – often the result of life-threatening gaps in care. Every two minutes, a woman or girl dies during pregnancy and childbirth. That’s despite our having the means to prevent such deaths and to improve maternal health substantially.

The just published United Nations’ Trends in Maternal Mortality report reveals that over the last few years, global progress on reducing maternal deaths has stagnated. We are now severely off course in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals target for reducing maternal mortality by 2030, and this is critically undermining women’s rights.

The report shows that between 2016 and 2020, only 31 countries achieved significant reductions in maternal mortality, whereas 133 saw progress stall, and 17 experienced an increase, including countries in almost all regions, at all income levels. Nevertheless, low-income countries bear a disproportionate burden of maternal deaths.

Inequity linked to income, education, and ethnicity is a key driver of these deaths. It propels health disparities, determining who has access to health-promoting services, resources, and opportunities. Of the 287,000 maternal deaths in 2020, nearly half occurred in the poorest regions of the world, where only 13% of people live. Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for a massive 70% of the global total.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the risk of dying during pregnancy or childbirth is 130 times higher than in Europe or North America. And in the nine countries deemed the most fragile by the Fragile States Index, the maternal mortality rate for 2020 was double the global average.

But even in advanced economies, there are huge disparities. For example, Sha-Asia Washington, a black woman aged 26, died during childbirth in Brooklyn, USA, in 2020. She suffered a cardiac arrest while her baby, Khloe, was delivered through an emergency c-section. Black women in the USA are almost three times more likely to die in childbirth than are non-Hispanic white women. It is little wonder that experts believe that maternal mortality won’t decline until racial bias is addressed.

Wherever they are in the world, some mothers are more vulnerable than others. Maternal mortality is characterized by a J-shaped curve, with adolescents at higher risk than women aged 20 to 24. A holistic “life course” approach is therefore essential, including interventions that address harmful gender norms and practices regarding adolescents, which all too often lead to child marriage, gender-based violence, and access being denied to sexual and reproductive health services and rights.

Access to high-quality care throughout life has a hugely positive impact across generations. Yet, some women are still unable to fully access critical maternal services. A third are not receiving even four of the recommended eight antenatal checkups, while 270 million lack access to modern family planning. Of the estimated 5.6 million abortions each year among adolescent girls, nearly 4 million are unsafe.

In much of the world, the issue is that maternal and newborn health is not prioritized enough. For example, between 2019 and 2021, development assistance for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health decreased by 2.3%. The speed at which maternal mortality is being reduced needs to be more than double the current rate in order to hit the 2030 SDG target. Further, these recent stark statistics on maternal mortality come at a time when women’s rights are increasingly challenged.

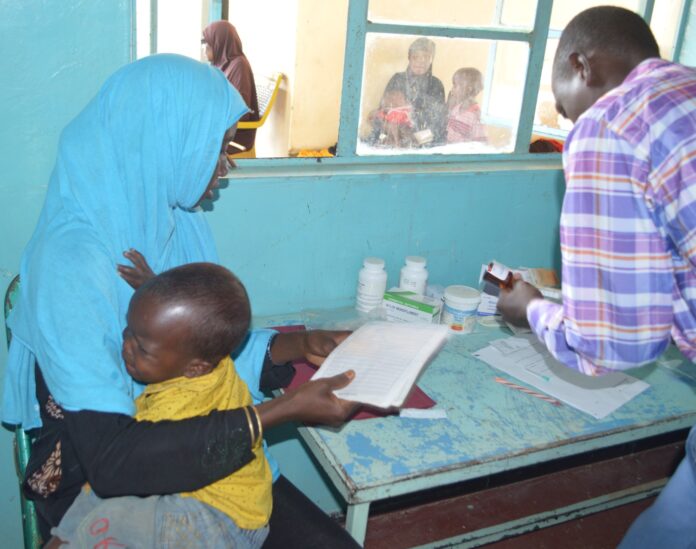

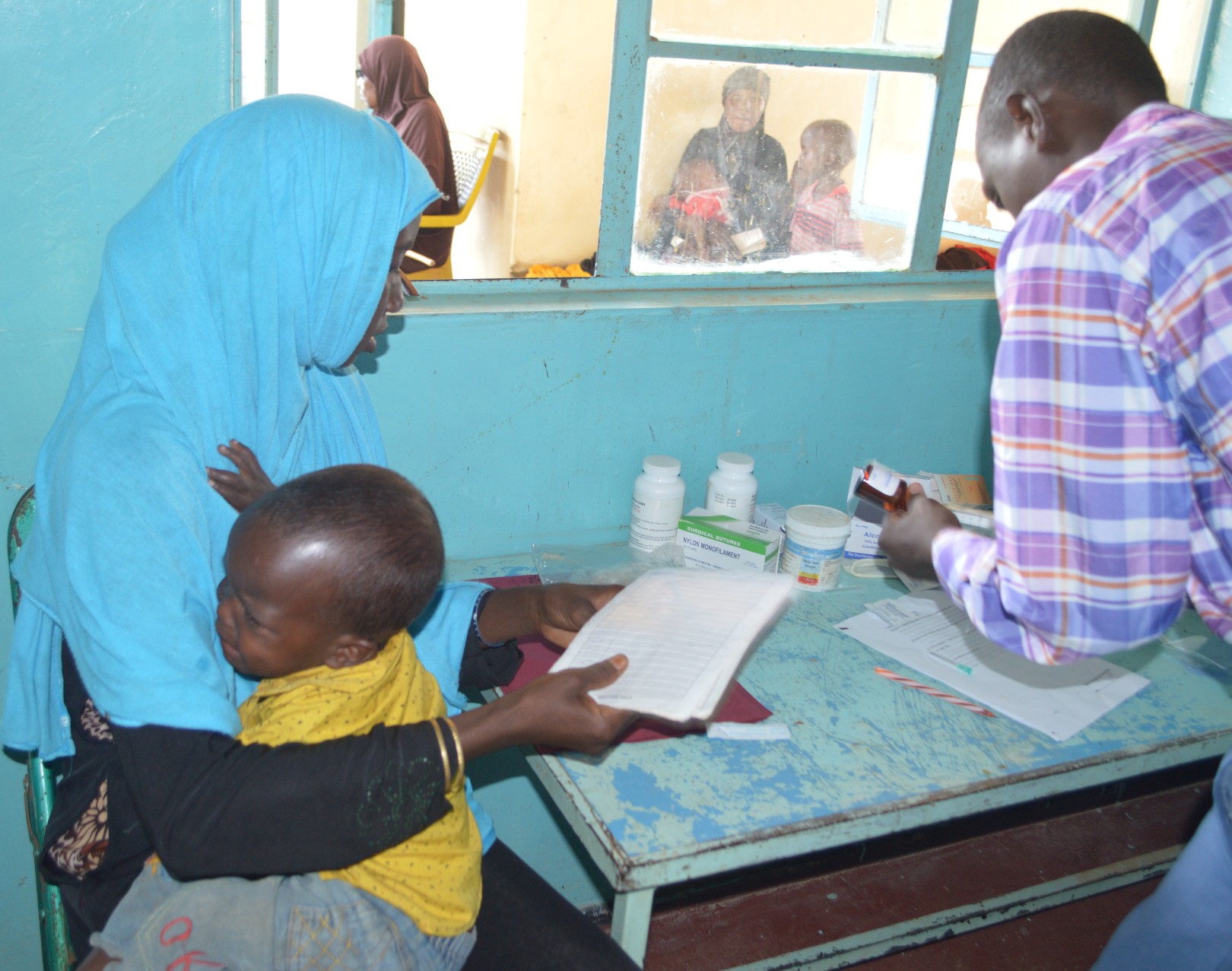

The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) and the World Health Organization are working with countries and partners all over the world to improve access to high-quality reproductive, maternal, and newborn health care services, prioritizing the poorest and most disadvantaged and marginalized communities which are carrying a disproportionate burden of preventable deaths.

We are working to ensure universal health coverage and accountability, address all causes of maternal mortality and ill health, and strengthen health systems so that they collect high-quality data and respond to the needs and priorities of all women and girls.

We have only seven more years to meet the SDG targets. We must intensify efforts to mobilize and reinvigorate global, regional, national, and community-level commitments. How many more women like Zainab and Sha-Asia must die, needlessly, before our message is heard? Our answer is this: Invest now, protect rights, and demand change. This is what it will take to end preventable maternal mortality once and for all.

Helen Clark is the Chair of the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (PMNCH) and former Prime Minister of New Zealand; and Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO).

This Op-Ed was originally published in The Telegraph.