|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By: Sharon Kiburi

Nairobi, Kenya: Women are known to be more prone to sexual harassment than men. Public transport spaces are reported to be a major contributing factor to sexual harassment and gender-based violence. Less awareness of the crime, little or no research, data, and vague/fewer guidelines and policies on the issue are also witnessed.

For example in Kenya, Nairobi, in particular, have more commuters using public transport than a private mode of transportation. According to a Deloitte study, Nairobi County, 696km2, has about six million people, about 46% commuters using public transport. Being the capital city of Kenya, Nairobi generally has heavy traffic flow with dense congestion, especially during peak/rush hours.

A recent rapid assessment report was launched on eighth June 2021 (18th June 2021) on sexual harassment in public transport places. The study shows that sexual harassment incidents are prevalent in Kenyan’s public transport sector, with 87.5% of commuters under the study had either witnessed or experienced sexual harassment. The most common type of sexual harassment that occurs in public transport spaces is verbal Abuse. The report was produced Kenya Youth Generation Equality Consortium.

The findings show that 41.67% of the respondents have witnessed/experienced verbal type of sexual harassment that includes suggestive comments, abusive language, or jokes that make victims feel offended. These cases (of sexual harassment/Abuse) are prominent at night compared to any other time of the day, and they majorly occur in public service vehicles.

The findings show that 41.67% of the respondents have witnessed/experienced verbal type of sexual harassment that includes suggestive comments, abusive language, or jokes that make victims feel offended. These cases (of sexual harassment/Abuse) are prominent at night compared to any other time of the day, and they majorly occur in public service vehicles.

Kenya has made progress in gender-responsive policies and laws. The Kenyan Constitution provides key legal frameworks for protection against gender-based violence. The Bill of Rights protects all citizens, including users of public transport. Laws such as the Sexual Offences Act, 2006, Penal Code, and National Transport and Safety Authority Act, 2012, among others, provide clear legal rights and enforceable actions to protect citizens against any form of sexual and gender-based violence.

In support of planning and investments around SGBV, several policies and strategies have been developed under National Policy on Gender Development (NGEC) 2019, NGEC Model Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) Policy, and Integrated National Transport Policy 2009.

These seek to promote professionalism in road passenger transport operations to encourage more private sector investment. While efforts have been made to develop critical laws and policies to reduce SGBV, particular attention to SGBV in public transport needs serious consideration.

On average, 242(36%)of 672 commuters are likely to encounter/witness 1-2 instances of sexual harassment/Abuse.29.3%, 16.8%, 4.0%, and 2.1% of the respondents are likely to encounter/witness 2-3,5-6, more than 8 and 7-8 times, instances of sexual harassment/Abuse while commuting. Only 11.8% of the commuters are confident they are not likely to encounter/witness any example of sexual harassment/abuse.

Julia (whose name has been changed to protect her identity) is from the Eastland of Nairobi-Kenya. Julia, who speaks with a small, faltering voice, tries to smile, but this does not entirely erase the pain in her eyes. She looks away, scratches her short hair, then she leans forward; tears start streaming down her cheeks, then she pulls out her shirt to wipe her tears. “The rape experience changed everything, to be honest; I am not the same person, he finished me,” she says.

On a fateful day, Julia was walking home one evening at around 6:45 in one of the slum areas in Nairobi after spending the evening with her friends. She had to get back home to prepare for the new week ahead. She made a living hawking a few items within Eastland’s. Sometimes, she worked as a “Kamagera”, a common name for touts stationed at a particular stage to help the principal conductor fill the vehicle. She felt it was getting darker, so she decided to board a “Bodaboda” (these are bicycles or motorcycles used as taxis” s for carrying passengers or goods familiar in Keny) to save on time.

The ordeal occurred when the Boda Boda rider requested Julia stop over at his place to get a jacket and embark on their journey quickly. She agreed to this request; as soon as they got into the compound, the rider promptly alighted and rushed back towards the gate and locked it. He then pulled her hair and dragged her to his house.

“He threw me on the bed face down. He pressed me down with his great weight, then turned me over on my back, tore open my shirt, jerked my bra up around my neck, unzipped my skirt, and pulled them down as far as he could. Over the next three hours, he raped me and tormented me with descriptions of how he would kill me using a knife, telling me exactly where he would cut me. He covered my face with a pillow and pressed it down so that I could not draw a breath nor shout out for help. Each time I expected to die, but he always relented just before I lost consciousness,” Julia narrated.

Further, Julia confides, “When I got home, I collapsed in the shower, bleeding and thinking only of the horrific ordeal I had gone through. I got up the following day as usual. I cleaned my bruises using warm water and salt and left for work. About two months later, I was struck down suddenly by unbearable abdominal pain. I threw up Profusely. I started to bleed and passed out.” Upon arrival in the hospital, she realized that she was pregnant with a baby boy from the rape.

“I become suicidal, and I was too toxic for those around me. I hated all men, and I lost several friends. There was no life left in me. I completely withdrew from society; I stopped working. I spent weeks in my house, hardly eating as depression overcame me. Many a time, I sat on the balcony contemplating suicide. I become a shadow of myself barely eating, constantly blaming myself for wearing a short skirt. This might have triggered him,” Said Julia. Her pregnancy

resulted in complications around her Fistula and a damaged vagina, adding more strain to her already challenging life.

Julia did not seek justice or legal action against the perpetrator, elaborating, “In the first few months after I was raped, my brain went numb. I dissociated and forced myself to forget this incident. I decided then not to report my rape; I just wasn’t high-functioning enough to have the thought to go ahead and do it. I knew that a child would be born out of rape, and I was careful not to get my child discriminated against by society. I have never shared this story with anyone,” said Julia.

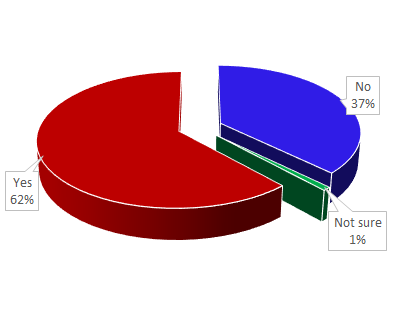

In efforts to explore sexual harassment at the watchdog’s work environment. A survey conducted in December 2020 by the Media Council of Kenya regulatory body and article 19, Eastern Africa, showed that sexual harassment is a hurdle many journalists have to deal with. Participants were composed of 61 (52%) females and 57(48%) males from print, radio, TV, and online platforms—the participants’ response to whether they have experienced or witnessed sexual harassment in their workplace sixty-two said yes, thirty-seven said no while one percent were uncertain.

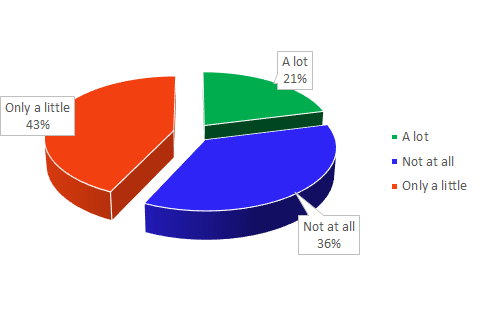

In response to whether Sexual harassment affected their work productivity, the answer was forty-three percent said only a little, twenty-one-per cent said a lot, and thirty-six percent said not at all.