|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Zippy Karani

Juba, South Sudan:In a shelter made of elephant grass and plastic sheets in the Protection of Civilians site (PoC) in Bentiu, northern South Sudan, a widow cooks for her children. Nyamal*, 43 years old, is preparing the traditional dish wualwual, a kind of porridge. Wearing a vibrant yellow dress, she sits on a short stool close to the entrance. This way, she can look at the kids playing outside and control the pot over the ember on the floor.

“I decided to come to the PoC in 2014 because Bimruok, in Bentiu Town, was not a safe place for my children. We could not stay in a war zone. If there were crossfires, everyone would be killed,” she says.

Armed conflict erupted in the country in December 2013. Like Nyamal, thousands of people were forced to flee their villages, seeking protection in the bases of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) in different parts of the country. Bentiu is the biggest PoC, today hosting around 97,300 people living in similar conditions to Nyamal.

Substandard living conditions and preventable diseases

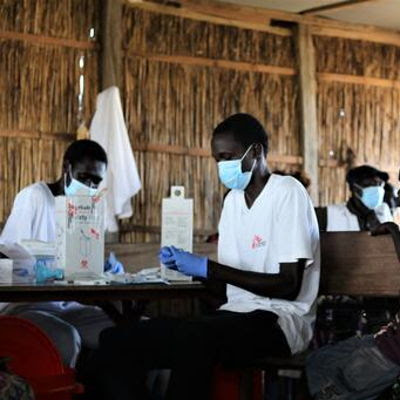

MSF runs a 116-bed hospital in Bentiu PoC with an inpatient department, emergency room for children and adults, as well as an operating theatre for surgery. The surgical patients include people from other parts of South Sudan, referred by MSF teams from projects in Pieri and Lankien and transferred by plane amidst ongoing violent clashes and fighting in Jonglei state.

The hospital also provides maternal care, including for complicated deliveries, as well as care for survivors of sexual violence, mental health care, treatment for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malnutrition. In 2019, more than 49,000 people (from inside and outside the PoC) received care in the facility. Since January to October 2020, MSF teams treated more than 80,000 people, most for malaria and respiratory tract infections. MSF also manages a water borehole for the community to use, and distributes soap and other hygiene items.

The hospital also provides maternal care, including for complicated deliveries, as well as care for survivors of sexual violence, mental health care, treatment for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malnutrition. In 2019, more than 49,000 people (from inside and outside the PoC) received care in the facility. Since January to October 2020, MSF teams treated more than 80,000 people, most for malaria and respiratory tract infections. MSF also manages a water borehole for the community to use, and distributes soap and other hygiene items.

In 2019, MSF conducted a survey in the PoC to evaluate living conditions. The study, which concluded in March 2020, showed that less than 60 per cent of families had their own water jug for cleansing after defecation. The risks to health posed by these substandard living conditions include diarrhoeal disease, hepatitis E, cholera, typhoid fever, trachoma and skin infections. Many can be avoided with improved water and sanitation – something that MSF has been repeatedly calling for.

Children under five-years-old are most vulnerable. Among those admitted to the MSF hospital in 2020, 562 were severely acutely malnourished, many also had other preventable illnesses, often they had been prematurely born because their mothers were also sick.

“Women cannot take care of the children full time because they spend hours collecting firewood outside the PoC or [carrying out] other manual labour to earn a living. It’s how they earn money to provide for their families,” explains Philippe Manengo, MSF hospital coordinator in Bentiu. “These kids often never had a clean place to sleep or play. The long-term exposure to chronic diseases, coupled with malnutrition, decreases their immunity, making them more susceptible for other illnesses.

“Women cannot take care of the children full time because they spend hours collecting firewood outside the PoC or [carrying out] other manual labour to earn a living. It’s how they earn money to provide for their families,” explains Philippe Manengo, MSF hospital coordinator in Bentiu. “These kids often never had a clean place to sleep or play. The long-term exposure to chronic diseases, coupled with malnutrition, decreases their immunity, making them more susceptible for other illnesses.

Despite all our efforts, this year we have lost nine per cent of the malnourished children in our hospital. It’s very distressful and concerning.”

An uncertain future

The peace agreement signed in 2018 renewed debates around returns of displaced people to their villages. In July 2020, UNMISS announced that it intended to start a process of handing over the five PoC sites in the country. It means the camps will remain, but with management and security responsibilities transferred from the UN to the national government. The announcement has prompted negative reactions from the people in Bor and Juba PoCs, where the transfer has already started, with many saying they were not informed of the UN troop withdrawal and now live in fear.

In Bentiu, MSF teams have been listening to similar concerns raised by patients and other community members, mostly about safety and security conditions once the UN is no longer there.

In Bentiu, MSF teams have been listening to similar concerns raised by patients and other community members, mostly about safety and security conditions once the UN is no longer there.

Nyakoang*, a 30-year-old woman, has been few times to the MSF maternity ward. She lives in a 16 square metre one-room accommodation shared between three families, eight people in total. She tells MSF her concerns: “This is not the kind of life I want for my children and myself. I want to be able to go to a place where I can study while my children are safe and that they can go to school. Education is what can change their lives.”

Nyakuoth*, a 50-year-old woman, from Rubkona adds: “The UN gathered people here and told us they will leave this site. We told them that if they leave there will be a damage. They didn’t explain how they will do it nor when it’s going to happen. I don’t know if we will be protected.”

Amidst the uncertainty, MSF teams reassure the community that medical care to the people of Bentiu will continue, regardless of UN protection status.

*Names changed