By Mary Mwendwa

Nairobi, Kenya: For Zephania Maberi, Uganda had become a too dangerous place to live. Being a gay man was against Uganda’s strict laws against homosexuality, so in 2019, Maberi decided it was time to leave his home country and flee to Kenya as a refugee.

But now Maberi fears the persecution and prejudice he’s now facing in his new country will prove to be no different than the situation he fled six years ago. More importantly, he also fears that Kenya’s proposed anti-homosexuality law means he will once again be branded a criminal simply because of his sexual orientation.

“I came to Kenya in 2019 because back home I was being harassed and rejected because I am gay,” said Maberi, who is 34. “I was facing constant threats, I feared for my life, and my mother was worried.

“My mother knew I was gay through other people”, he said. “Although at first, she embraced me, she slowly started feeling worried about my life because of pressure from the community we were living in.”

“The threats and discrimination became too much and my mother advised me to leave Uganda for the sake of my security. She feared I would be attacked and maybe killed.”

Uganda has criminalized homosexuality through prohibitive laws while Kenya has made attempts to do the same, through the proposed Family Protection Bill -2023 drafted by Hon. Peter Kaluma, which has been cited as an unconstitutional law similar to the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Bill.

The Constitution of Kenya (2010) prohibits discrimination of all individuals. It further provides rights to equality and freedom from discrimination and human dignity and freedom in articles 27 and 28 respectively. Similarly, Article 56 provides minorities and marginalized with the right to affirmative action for education, employment, and development.

Maberi is one of many refugees who feel stranded in Kenya because of their home countries’ harsh laws that criminalize homosexuality. They watch the growing intolerance in Kenya with alarm.

Maberi who lives with friends in one of Nairobi’s low-income areas, describes the suffering he endured when he first arrived in Kenya and settled at the Kakuma refugee camp. He said he was constantly attacked by other refugees at the camp who learned of his sexual orientation.

Pointing at scars on his hands and back, Maberi shakes his head as tears fill his eyes as his journey of seeking a safe haven started in 2019.

After the Ugandan government enforced the Homosexuality Bill in 2019, Maberi said life became very difficult. He left after his mother told him she feared her life was being put in danger because of her son’s sexual orientation. He eventually relocated to the Kakuma refugee camp with two of his friends.

“We stayed at the reception in Kakuma for one month and were later taken to the refugee community within Kakuma.” Maberi said.

He says officials at the camp knew about their orientation as gays and therefore they could not freely mingle and associate with other refugees. But even before that, some of their friends had been evacuated from Kakuma due to constant attacks from other refugees within the camp.

“At the camp, we had stayed for one month at reception without any documentation forcing us to stage a demonstration at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) offices. We were beaten badly by the police, with some of us getting life-threatening injuries,” he added.

The camp life was very tough. “We were constantly attacked and discriminated against even by workers,” he said. “Some of the workers would tell us that they did not need gays at the camp. By that time very few of us could understand Swahili which was the main language at the camp.”

By 2020, Maberi said, the attacks had escalated to extreme levels.

“We decided to hold another protest for us to be evacuated to safety,” Maberi said. “Sadly, we were met with hostility and accused of playing victim so that we could be relocated aboard for better opportunities. We stayed outside the UNHCR offices for one week where police came and forcefully took us and dumped us again at the camp.

“At the camp, refugees from other countries would attack us and damage our tents which left us exposed and more vulnerable. They beat us and at times, some of my friends got raped.”

Maberi claimed the incidents were reported to the police but no action was taken. Instead, the police at the camp demanded bribes to investigate the cases. (Maberi’s claims could not be verified because he did not have the OB number at the time of his interview.)

Maberi describes one particularly violent attack that was instigated by other refugees at the Kakuma camp in 2020.

“They attacked us with all manner of crude weapons including knives, stones, and physical beatings,” said Maberi. “We tried to fight back but they overpowered us and most of us were injured badly.”

“During the attacks, they would tell us ‘hatutaki shoga hapa.’ It means we don’t want gays here. I still have those scars on my body to date. We reported the attacks to UNHCR but no action was taken.”

After that attack, Maberi left for Nairobi. But he says the situation there isn’t much better.

“I do not openly display myself as a gay person,” Maberi said. “I fear I may be attacked by the public. I live in constant fear even after leaving the camp.”

Because he hasn’t received an alien identification card, he can’t access services, such as banking, visit a hospital, or find employment.

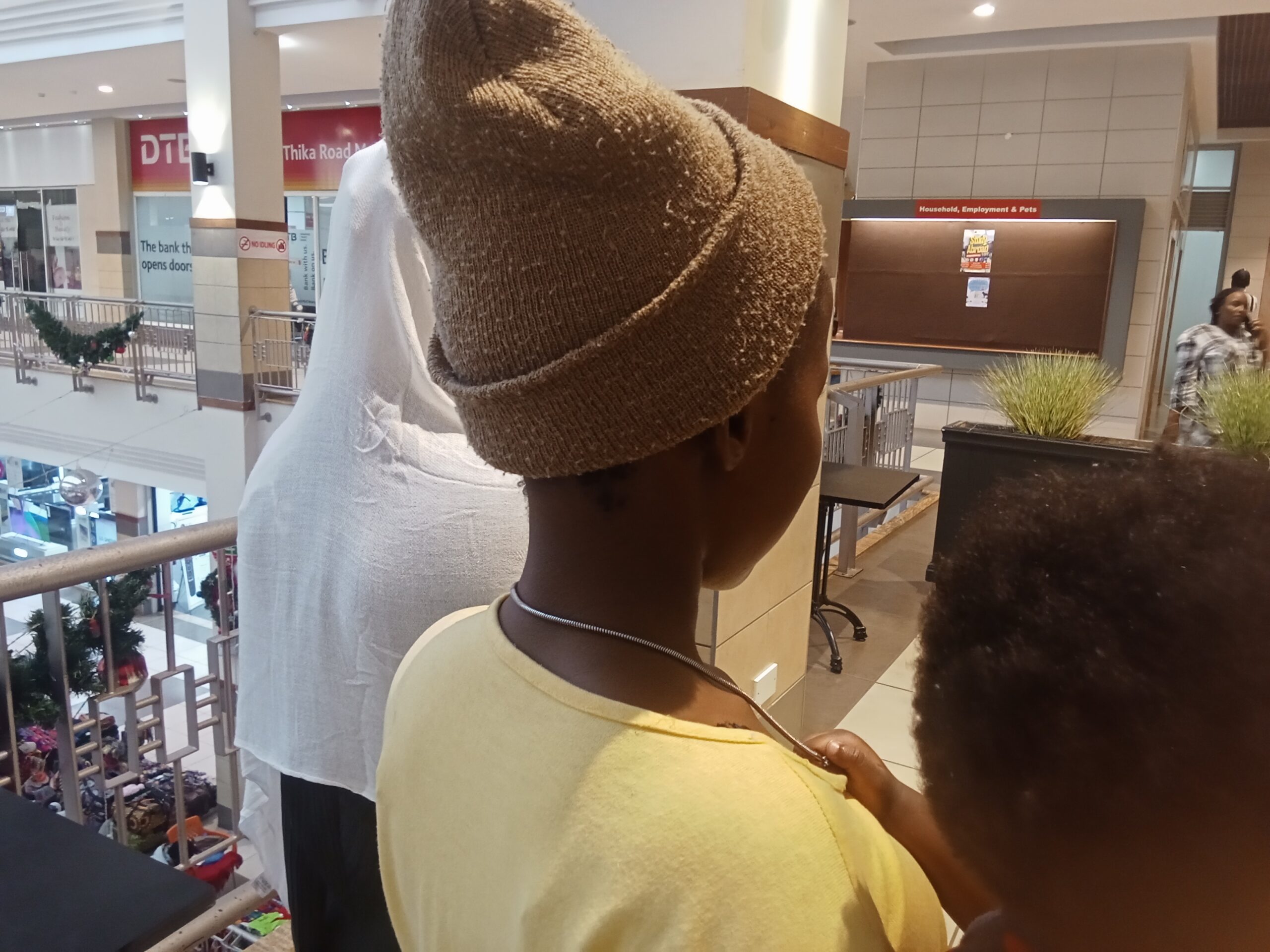

Angelique Uwababyey arrived in Kenya from Rwanda in 2020. She is 22 years old, a mother of one, and a lesbian refugee now living in Nairobi.

Uwababyey who speaks fluent Swahili, Luganda, and her native language from Rwanda, is also a survivor of attacks and rape while living at the Kakuma refugee camp.

She displays a scar on her forehead which was the result of an attack at the camp after other refugees confronted her over rumours circulating that she was a lesbian.

As her toddler breastfeeds, Uwababyey describes the challenges she has experienced as a refugee who identifies as lesbian while raising her child as a single mother.

“Life is very tough,” she sighed. “My baby needs milk and other needs. I struggle to get even the smallest casual jobs because I do not have an alien Identity Card.”

“Last year my baby was very sick. He had a breathing problem. I did not have money to take him to hospital. My fellow refugees contributed some money for the treatment. It was tough.”

Uwababyey fled to Kenya with her father and two brothers, who were also members of the LGBTQIA+ community. “We decided to come to Kenya because our mother rejected us and told us to leave the homestead,” she said.

“At the camp, as usual, we faced discrimination, attacks, and other human rights violations,” she said. “We resorted to sleeping in the middle of the tents as a safety mechanism to avoid being cut by Knives while sleeping.”

Uwababyey got a casual job as a bar attendant within Kakuma, where she would hide her lesbian identity to fit in and avoid suspicion from the public. She also dated men to conceal her status further.

One day while working as a bar attendant at Kakuma, she claims some men bought her a lot of alcohol that she now suspects was drugged. She was raped, became pregnant and decided to have an abortion.

“I feared to report the rape case,” she said. “I knew no help could come my way.”

She moved to Nairobi in 2022 and found another job as a bar attendant.

“I started dating a man to avoid more problems, the man became my boyfriend and we dated for a few months,” Uwababyey said. He impregnated me and took off. I have a one-year-old baby that I am struggling to feed with no proper job or shelter. Police harass us alot even here in Nairobi, when they ask us questions and they hear our accents they get an avenue to harass us and ask for bribes.”

Uwababyey said she receives perhaps KSH 500 every two or three months from community-based organizations that advocate for refugee rights as well as UNHCR. Occasionally, she`ll also receive sorghum, oil, and beans.

Her father and two brothers are still at the camp and she says they are often attacked and discriminated against because they belong to the LGBTQIA+ community.

“My dad is now sickly, he is diabetic and 68 years old,” she said. I struggle to get some money and send him something small. Life is tough for me. I am almost losing the small hope I have been hanging on.”

Victor Nyamori, a global researcher and advisor on refugee rights for Amnesty International, said the LGBTQIA+ refugee community in Kenya is not well protected.

The host community is extremely violent towards the refugee LGBTQIA+ community,` Nyamori said. He described an occasion when one person died after a petrol bomb was thrown into one of the houses where an LGBTQIA+ refugee lived.

“We have documents of various forms of violation including physical attacks, beatings, and stoning meted on them,” said Nyamori.

They have bad experiences at registration and even when they want to leave the country.

“Some of the most persistent challenges that we have seen as an organization are around registration,” Nyamori added. Most of them say that they are harassed during that process. Some officials don’t believe those of transgender nature, asking them to prove their sexuality.

“We are constantly receiving cases of attacks from refugees from Ethiopia, Somalia, and Uganda which has criminalized LGBTQIA+, Rwanda, and Burundi among others.”

A joint detailed report titled “Justice Like any Other”- Hate Crimes and DiscriminationL against LGBTQIA+ Refugees by the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission and Amnesty International documented extremely dangerous hate crimes, discrimination, and other human rights violations suffered by lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and intersex asylum seekers and refugees especially those living in Kakuma refugee camp between the period of 2018-2023 respectively.

The findings of the study point out a disturbing picture of how refugees and asylum seekers have suffered assaults, threats, and intimidation in Kakuma camp, most of them more than once, because of their sexual orientation, gender identity, and/or expression and sex characteristics.

The report further reveals that in most cases the attackers referred to their targets’ sexual orientation, gender identity, and/or expression and sex characteristics either directly, often using derogatory terms for “gay” or “lesbian”, or indirectly, for example asking them to kiss a person of the same sex or claiming them to be a “curse”, that is bringing harm to the camp.

John Burugu, the Commissioner for Refugees and head of the department that deals with refugees did not respond to an email request for an interview.

In response to a WhatsApp message also seeking an interview, Burugu declined to participate. He also declined to provide any other official from the department for an interview opportunity.

In a statement, the UNHCR, Kenya said some LGBTQIA+ refugees in Kakuma may face challenges rooted in societal stigma and discrimination, compounded by Kenya’s legal context, which criminalizes same-sex relations. “These individuals may therefore encounter heightened protection risks, and rights violations and they may choose not to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity, even during the registration process, which limits targeted assistance.”

The UN Refugees Agency outlined how it monitors and responds to security incidents involving refugees and asylum seekers in Kakuma, including those with an LGBTQIA+ profile. “Mechanisms such as a toll-free helpline, partner-managed reporting channels, and email accounts are in place to ensure incidents are reported and addressed promptly. Each case is managed in coordination with law enforcement and relevant partners, with survivors receiving legal assistance, psychosocial support, and other necessary interventions. While specific statistics may not be publicly available, these systems aim to address individual protection concerns effectively. UNHCR also engages in community dialogue to reduce tensions and promote coexistence.”

The agency says that the security and well-being of refugees, including those with an LGBTQIA+ profile, remains a key priority for UNHCR and its partners. “LGBTQIA+ refugees residing in Kakuma have free and non-discriminatory access to services offered to all residents, including shelter, food, core relief items, counseling, healthcare, and specialized gender-based violence (GBV) services. Safe spaces, such as drop-in centers, are available to LGBTQIA+ refugees for accessing healthcare and support. Additionally, specialized training has been provided to service providers to ensure non-discrimination during service delivery.”

With respect to registration challenges faced by some of the refugees, the agency notes that the Kenyan government’s Department of Refugee Services (DRS) is fully responsible for conducting registration and refugee status determination (RSD) in Kenya. While UNHCR provides technical support to the process, UNHCR does not have the authority to expedite the processing of specific cases.

“There are currently more than 219,000 asylum-seekers whose refugee status has not yet been determined, including many with an LGBTQIA+ profile. UNHCR continues to advocate for measures to improve the efficiency of the process and to address the backlog, and requests expedited decisions in cases involving individuals with heightened protection concerns or pending applications for durable solutions, including those with an LGBTQIA+ profile,” a UNHCR official said.