By Clifford Akumu

Narok County, Kenya: Sustainable Development Goal number 13 targets the world to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

A deeper dive into the SDG Report of 2022 further paints a grim outlook with indications that by 2030, an estimated 700 million people will be at risk of displacement by drought alone.

Kenya is not an isolated case either. In early February this year, for example, the country had been experiencing some of the worst drought conditions in decades, causing loss of livestock, wildlife, crop failure, biodiversity, and malnutrition.

The U.N. humanitarian agencies termed the drought in the region a “rapidly unfolding humanitarian catastrophe.”

And by the time the long rains typically from March to May began, approximately 5.4 million people in Kenya were projected to lack adequate access to food and water between March and June according to the International Rescue Committee.

According to the humanitarian body’s estimates, the drought situation had resulted in the death of over 2.4 million livestock, a heavy blow to pastoralist communities who largely depend on them for income and food.

“The drought is worsening. International agencies have predicted low rainfall during the March-May season that is ongoing,” said Siati Ali Amin, executive director at Horizons Analyst and Researchers Network.

“And this will translate to a sixth consecutive below the average rainfall season in the ASAL regions with the number of people affected by food insecurity might increase from 4.5 million to probably 5.8 million as projected by the experts.”

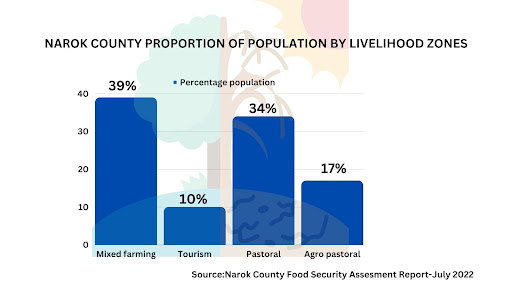

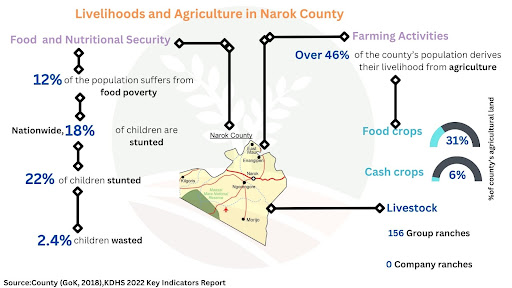

Narok County has more than 1.1 million people according to the 2019 census with four main livelihood zones including pastoral, agro-pastoral, mixed farming, trade, and tourism.

It is one of the drier counties in Kenya. Narok South where the Narosura community is situated is vulnerable to climate change. This means the lowlands experience water shortages which put pressure on the available water resources.

Prolonged dry spells and periods of drought have reduced the availability of pasture, and pastoralists are now struggling to feed their animals.

In the arid, desolate landscape of Narosura-marked by miles and miles of acacia trees and dust-we meet Mr. Eric Setek busy in his patch of the luscious green plot.

We arrived at Setek’s farm on a searing afternoon where we met him tending to tall and luxuriant tomato plants, which he has intercropped with cabbages and maize planted in neat rows on the edges of the plot.

Setek is a smallholder farmer from Narosura in Narok South, a semi-arid lowland mainly inhabited by the pastoralist Maasai Community.

A last born in a family of six, Setek is part of a 21-member Oloibor-oing’oni farmers group that recently embraced horticultural farming, abandoning an old practice of leasing farmlands to foreigners.

“As a pastoralist community, we have for the longest time leased farms to foreigners to farm on. We charge them Sh8,000 an acre for a six months lease period. They produced food that as a community we ended up relying on for our food security. But they gain so much in return,” explained the 23-year-old Setek.

This is a huge cultural shift and one, the farmers say-is a shock of a lifetime.

Due to their nomadic nature, Maasais like Setek has long been known to lease their land to be farmed by other people from as far as Tanzania and Uganda. He had 30 livestock but lost more than half to drought.

“Instead of continuing to keep livestock and sometimes lose all the stock to prolonged drought, we decided to make good use of our land and venture into farming for food security,” added Setek.

During the drought season,Setek would be on the border of Kenya and Tanzania in Loita, herding his cattle. Not anymore. On this day he was busy weeding a section of his young tomato crop and soon his maize will be ready for harvest.

This means from December last year, the father of two, now remains in the village to tend to his tomatoes — disrupting his earlier nomadic lifestyle. Climate change is slowly eroding Maasai’s traditional nomadic culture.

Like several other Maasai men within Narosura village, prolonged drought has rendered traditional graze lands untenable because, the weather is no longer promising us grass, and the short rains can barely sustain some crops in my area-said Setek who relies on irrigation for his crops in a one-acre farm.

According to the January 2023 National Drought Early Warning bulletin produced by the National Drought Management Authority(NDMA),Narok County was in the alert drought phase.

The bulletin further revealed that the drought situation was critical in 22 of the 23 ASAL counties due to the late onset and poor performance of the much-anticipated October to December 2022 short rains, coupled with previous consecutive failed rainfall seasons.

As the dry spells in the county became prolonged and severe, rainfall became intense and short-lived.

Pasture and livestock browsing conditions have deteriorated in Narok,Baringo,Isiolo,Garissa, Mandera, Kajiado, and Kwale counties according to the agency. Consequently, the body condition of cattle and goats ranges from fair to poor as a result of long trekking distances in search of water and pasture.

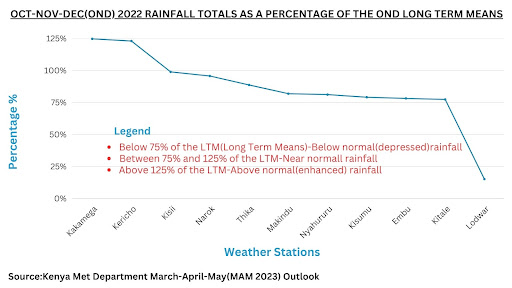

The seasonal rainfall analysis from 1st October to 31st December 2022 (short rains) by the Kenya Meteorological Department indicated that depressed rainfall was received in most stations over the Southeastern lowlands, northwestern, North-Eastern, and Coast.

Several counties recorded near-average rainfall with Narok recording (95.7%),Kakamega(124.7%),Kericho(123%),Kisii(98.9%),Thika(88.7%),Makindu(81.9%),Nyahururu(81.2%),Kisumu(79.1%),Embu(78.2%),Kitale(77.4%) with Lodwar recording the lowest at 15.2% as a percentage of the October-November-December Long Term Means(TLM).

The county would further receive depressed rains, in February, that was poorly distributed in time and space across the livelihood zones according to the NDMA bulletin.

Narok recorded an average of 5.54 and 6.56 millimeters of rainfall in the first and second dekad of February 2023 compared to 17.70 and 28.90 normally respectively, according to World Food Program-VAM,CHIRPS/MODIS data.

As the dry spells in the county became prolonged and severe, rainfall became intense and short-lived. The changing weather patterns eroded the value of livestock at Narosura market.

Currently, livestock farmers need to sell a total of three livestock to be able to meet expenses, such as school fees for one child.

“But with tomatoes and cabbages all year around from my farm, I’m now able to sell the produce and get school fees for my two children with ease,” noted Setek.

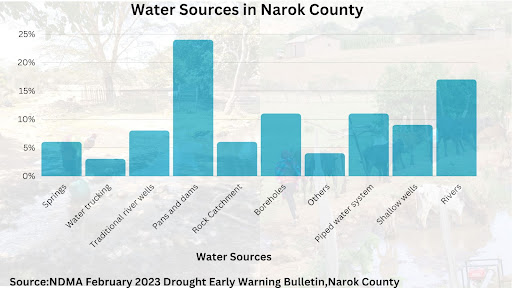

There are three main sources of water for domestic use in the county including; pans, dams, rivers, shallow wells, other boreholes, and traditional river wells.

The major water sources for both human and livestock consumption during the month of February were pans and dams, rivers, and boreholes alternating with piped water systems according to NDMA.

Pans and dams were relied on by 24 percent of the households while rivers and boreholes/piped water systems were each relied on by 17 and 11 percent of the households respectively.

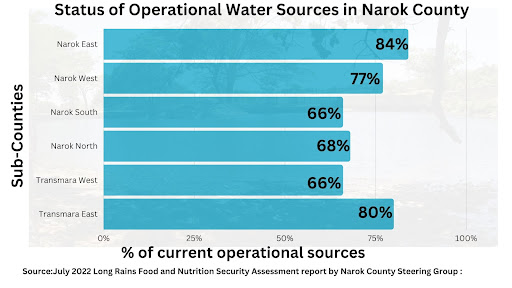

According to the July 2022 Long Rains Food and Nutrition Security Assessment report by Narok County Steering Group and Kenya Food Security Steering Group, lower parts of Narok South and East had the lowest number of water points due to vastness and poor accessibility.

About 73 percent of boreholes are operational across the livelihoods with most non-operational being in Narok South and West sub-counties due to mismanagement and collapse of management committees, theft or breakage of solar panels, breakdowns, and dilapidated infrastructure.

Like other members of Oloibor-oing’oni farmer’s group, Mr. Setek relies on the water from Enkong’u Enkare (locally known as the eye of the water) spring-a critical freshwater source for his irrigation.

The wetland is the source of river Narosura that supports farming from the upstream to the downstream, serving in its wake more than 15,000 households.

To solve water-related conflicts and regulate the amount of water used for irrigation activities,Narosura Water Resource Users Association (WRUA)supported by the Water Resource Authority in Narok County was formed.

James Ole Tago, secretary Narosura WRUA noted that the water catchment area also supplies water for domestic use downstream for schools, health, and shopping centers within the community.

“Were it not for this water, people wouldn’t have lived here, because the place is so dry. And because of the multiple water uses, the spring needs more protection than any other wetland,” noted Mr. Tago.

The water from the spring serves both Oloibor-oing’oni and Narosura irrigation schemes. Farmers grow mainly fast-maturing horticulture crops, such as tomatoes, onions, cabbage, maize, and bean crops.

“We are proud farmers contrary to an earlier way of life because part of the fresh horticulture produce we get from our farms serves various town markets, as far as Nairobi, Kisumu,Bomet, and Kisii,” said Jeremiah Takona a member of the group who was once a pastoralist.

The farmer’s group began growing tomatoes and maize in December last year. They have already harvested and sold their first batch of tomato produce raking in some Sh120,000 profit.

“We intend to use this money to expand into other areas . We will then sit down together as a group and decide on how best to share this money amongst ourselves after deducting all production expenses when we finally finish the harvesting of the tomatoes,” said John Takona. chairman of Oloibor-oing’oni farmers group.

During dry seasons, when the water volumes in the spring reduce, Narosura WRUA advises farmers to prepare a small portion of the land to enhance the uniform allocation of water in each plot of land.

“I water my crops twice a week according to the schedule laid out by the WRUA. The farmer group has also drawn a timetable for members that are tasked to oversee the process. We use pipes to pump the water for irrigation,” said Setek.

Setek sells a full crate of tomatoes at the range of Sh15,000-17,000 depending on the market rates and harvests twice a week. One cabbage goes for Sh100 and a sack of maize fetches him Sh6,000 at Narosura market.

Narosura market/Clifford Akumu.

Narosura market/Clifford Akumu.

“My livelihood has changed since I ventured into farming. I’m able to take my children to school. I’m looking forward to increasing my livestock and opening a new business,” added Eric.

But high costs of farm inputs and pesticides might derail his target in the farming venture so they are forced to just farm on a small portion of the land that they are able to afford.

Mr. Bob Aston, project officer at Arid Lands Information Network(ALIN) which promotes climate change adaptation practices in East Africa, urged both the national and county governments to increase budgetary allocations towards agriculture.

“Most of the communities in ASAL areas are pastoralists, but we also have those practicing crop farming. When you look at the budgeting at the national level we have not reached the 10 percent target. At the ASAL counties, a lot of emphases is made on livestock. With the drought situation, we have reached a point where we need to put more allocation towards the agriculture sector because we really depend on rain-fed agriculture.” said Mr. Aston.

“We need to lay more emphasis on irrigation-particularly drip irrigation.”

According to the Kenya Meteorological Department Climate Outlook for the long rains (March-May 2023 ) published in early March showed that the depressed rainfall over most parts of the country is likely to negatively affect agricultural production in South Rift Valley and Southern lowlands.

The weatherman in its outlook further advised farmers to plant drought-resistant and early maturing crops, fodder, and pasture and liaise with the Ministry of Agriculture for appropriate land use management practices.

Alston further challenged farmers like Setek to embrace fodder production to mitigate the effects of drought on their herds.

“Pastoralists and farmers now need to become serious with issues of fodder farming because the weatherman has already warned that there are some ASAL places that will receive below-average rainfall,” Mr. Aston added.

During dry periods, farmers in Narosura experience big challenges, because the water volume reduces drastically. Sometimes the water is rationed, by closing it at night to allow farmers downstream to access the water.

“Although we have water, the farms are too many meaning the water has to be rationed. The national government helped us by laying pipes to allow the water to move with pressure. Earlier, we used to rely on canals for irrigation and we pumped the water using generators from a small dam after diverting the water from the canals,” said Setek.