|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Mercy Odada

Kenyans for a long time, have had to conform to the idea that information was a privilege of a few powerful bureaucrats both in private and public institutions. Journalists and civil society organizations who sought information were intimidated by invoking the Official Secrets Acts of 1968.

In November 2015, the late Interior Cabinet Secretary Joseph Nkaissery ordered the arrest of Nation Newspaper parliamentary Editor John Ngirachu, Standard Group journalist Alphonse Shiundu and James Mbaka of The Star who published stories questioning how Sh3.8 billion was spent by his ministry. They were threatened with detention if they failed to reveal their source of information which the police claimed was privileged.

However, things look promising for President Uhuru Kenyatta signed on August 31, 2016

Access to Information bill into law, making Kenya the 21st country in Africa to move in that direction.

While this is good news for all Kenyans, the biggest benefactors are journalists, civil rights groups and activists who have long had an antagonistic relationship with public officials and corrupt private entities with regard to sharing of information.

According to Sheila Masinde of Transparency International (TI), there is a need to have an

implementation framework now that the law is in place.

Journalists have suffered effects of denial of access to information from public offices for

reasons which include documents labeled confidential, top secret and classified to bar Journalists from informing audiences accurately on issues that affect them.

With the law in place, Journalists can now seek information to inform the public on matters of public interest.

Fact checking

Fact checking what public figures have said versus the numbers on record “Information makes sense when put into context and what it means for service delivery “ noted

Erick Mugendi of Pesa Check.

According to a report by Article 19, Kenya: Realising the Right to Information(2014)access to information allows individuals and groups to understand government policies and the decisions governments make relating to health, education, housing, and infrastructure projects, as well as the factual basis for such decisions.

This makes it a basis for stakeholder engagement, and a key lever for good governance, transparency, accountability, and rule of law.

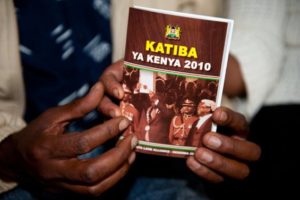

Sheila Masinde of Transparency International further argued saying “The Act puts to rest the long debated issue of government departments withholding information they viewed as from the public. It gives effect to article 35 of the constitution”.

Article 35 of the Constitution and Section 96 of the County Government Act, 2012 provide for the right to access of information. Article 35(1)particularly guarantees all Kenyan citizens the right to access any information held by the state or information held by another person and required for the exercise or protection.

However, despite the fact that the right to access to information is guaranteed in the

Constitution, there were still be challenges as far as actualizing the right is concerned.

Public servants, state officials and people who work in corporations that undertake public

functions had no clarity on what they can do to help citizens actualize the constitutional

provisions. The Act provides the framework for implementation of the constitutional provisions.

Who to give information

According to the act, public entities are obliged to make information public on request include those which receive taxpayer funds, companies which provide public services such as telcos and banks, and those exploiting natural resources such as oil and mineral wealth.

The provision of accurate information gives individuals the data and knowledge they require in order to participate effectively in the democratic process in any politicized society

Sheila Masinde of Transparency International argued that the Act places an obligation on public agencies to explain their actions, policies or decisions to citizens if they seek an explanation.

Winnie Tallam from the Ombudsman’s office said the new law also benefits individuals seeking information from public bodies in government.

Information officers

Whilst the law by default identifies the CEO of a company as the information access officer,

firms are required to do to comply with the Act is appointing a dedicated information access

officer — who will process requests for information by the public.

Companies, as well as State agencies, are also required to have a tab on their website clearly marked Access to Information where members of the public can lodge requests online.

Henry Maina, Article 19 regional director in charge of Eastern Africa, said public bodies must be at the forefront of implementing the access to information laws saying “According to the Act public officers are required to disclose information without the need for the

applicant to give reasons for requiring information. However private entities are only required to do so if the information is needed to protect a right or freedom”.

Who can seek information?

Before enactment of the law, the High Court of Kenya had ruled that corporates had no right to seek information. In the Nairobi Law Monthly v Kengen case, Nairobi Law Monthly, backed by lawyer Ahmednasir Abdullahi, took KenGen to court for failure to avail information relating to a disputed tender for drilling geothermal wells.

The High Court clarified that the right to information can only be enjoyed by natural persons, and not corporate bodies. “A natural person who is a citizen of Kenya is entitled to seek information under Article 35(1) (a

“The Court found that a corporate body or a company was not a “citizen” for the purposes of Article 35(1) (para. 82). Therefore, the petitioner, as a legal person, could only enjoy the rights of the “persons” conferred by Article 35(2), but not of the “citizens” conferred by Article 35(1), including the right to access information (para. 81)”

However, the acts now states clearly that ” A citizen “means any individual who has Kenyan

citizenship, and any private entity that is controlled by one or more Kenyan citizens.

This, therefore, means media houses or civil society organization can now seek information as corporate entities.

Awareness creation

A culture of secrecy still persists in most public bodies. Poor maintenance of records and

information, a lack of adequate funding, and a lack of public awareness of the right of access are all obstacles to openness in Kenya.

According to Winnie Tallam from the Commission of Administrative Justice, the organization

is educating public officers to understand the act “We have trained county secretaries and information directors from the forty-seven counties and doing in-house training for various ministries this will help public officers understand what is required of them” said Winnie.

“The enactment of access to information act found people who have a culture of secrecy in

office and perhaps do not know what to do with it, therefore the media can help unpack the act by going the extra mile” Christine Nguku a veteran journalist.

Protection of person making disclosure

The Act also seeks to protect public officers who may be victimized by disclosing information which is in public interest.

It states that a person shall not be penalized in relation to any employment, profession,

voluntary work, contract, membership of an organization, the holding of an office or in any other way, as a result of having made or proposed to make a disclosure of information which the person obtained in confidence in the course of that activity if the disclosure is of public interest.

According to Christine Nguku, as much as the right to access information is guaranteed in law, journalists need to make sure that they are cleared by having their National Identification, accreditation card from the Media Council Kenyan when seeking information.

Hold on

Even though the passage of the Access to Information Act guarantees citizens’ right to access and receive information freely, it is quite often not the case in practice. There are a number of prohibitive acts that conflict with the law in many of the African countries that have passed it.

For instance, Ethiopia which passed its freedom of Mass media and Access to information in

2008, but yet to publish ministerial guidelines to actualize the law and the enforcement of

national laws that contradict this provision claw back on this guarantee.

These include broad definitions for “terrorist acts”, ambiguous offenses such as “moral support and encouragement of” “terrorist acts” that grant the State broad discretion to criminalize dissent where there is no direct call for engagement in terrorism and where there is no likelihood of such acts occurring. In this regard, many journalists and bloggers have been jailed for long periods.