By Joyce Chimbi

Nairobi, Kenya: Growing up, Njoki ‘Kijo’ believed that her options in life were limited. By the age of 10, she had already lost her mother and was living in Kosovo, in the sprawling informal settlements of Mathare, with her grandmother, when danger came disguised as opportunity.

Sixteen and out of school, her family barely making it in a fragile cycle of hand-to-mouth, she joined a group of young women, and together, they ventured into Nairobi’s nightlife. This was 15 years ago. Still a child, her life in Nairobi’s red-light district began where 9 percent of female sex workers are under 18 years old according to data by Partners for Health and Development in Africa.

“Not even the tears of my distraught grandmother would change my mind. What else was there to do besides being a house girl, which I was determined not to do? Grandmother warned me that my mother made a similar journey to Mombasa and returned with Mukingo (a prolonged thin neck). When they said you had Mukingo, they meant HIV/Aids, and though too young to remember, she said my mother was buried in a polythene bag,” Kijo explains.

Modest estimates show that Kijo is one of 207,000 female sex workers (FSW) in Kenya, as per the most recent mapping of female sex workers nationwide conducted in 2018, to improve access to critical HIV and Sexual Reproductive Health Services (SRHR) among key populations in Kenya. The government, through the Ministry of Health, determines who qualifies to be classified as a key population.

She says the figure does not accurately capture the magnitude of sex work in Kenya, as many in the industry fear being identified as such due to the very negative attitudes and condemnation that come with being a sex worker. Yet, a focus on sex workers and other HIV infection at-risk groups is critical. Kenya has the fifth-largest number of people with HIV-1 in the world. Moreover, HIV is a centralized epidemic among Key Populations.

“In all countries or settings, you will have a certain group of people that are at much greater risk of being infected with HIV and of transmitting it. In Kenya, these are sex workers, men who have sex with men, transgender persons, and people who inject drugs. It also includes people in prison and other restricted or closed settings. They are vulnerable because their drug use, sexual orientation, identity, and behavior is largely criminalized, complicating access to comprehensive HIV and SRHR services,” D.S. Waithaka, an HIV clinical officer, explains.

“Consequently, key populations live on the margins of society and are left behind in health programming due to discriminatory policies, social stigma, and sexual and gender-based violence. Key populations do not have equitable access to quality, safe, and effective HIV and SRHR services. This is a double-edged sword as their heightened risk of HIV infection translates to a heightened risk of HIV transmission in the general public.”

For this reason, Patriciah Jeckonia, a Program Manager at the organization, says LVCT has been implementing programs designed for key populations, particularly men who have sex with men, since 2004. LVCT was also the first organization to establish a Drop-in-Centre (DiCE) nationwide.

A health policy expert and HIV prevention advocate, Jeckonia, says DiCEs are prevention centers or hotspots—areas where key populations are found in the community—providing comprehensive services such as HIV prevention, care, and treatment. DiCE clinics are essentially similar to any other HIV clinic, but they have a marked difference that sets them apart.

The Ministry of Health released the Standard Operating Procedures for Establishing and Operating Drop-In Centers for Key Populations in Kenya in November 2016. DiCEs co-located with clinics provide a one-stop shop for HIV testing, counseling and treatment, screening and treatment for STIs, family planning, pre-and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), cervical cancer screening, peer education, condom and lubricant promotion and distribution, medically assisted therapy, and much more.

There are also DiCEs that do not offer health services and are merely recreational centers for keeping populations to meet, interact, and build a community. The brick-and-mortar of a DiCE that is co-located with a clinic is similar to any other health clinic and is set up with approval from the government, following all protocols and procedures that dictate the running of a health facility.

A DiCE is a health facility – a certified clinic operated by qualified health providers who would have received additional training in differentiated health care provision and have the adequate skills to provide services to a particular cohort of people – in this case, key populations. DiCEs are set up close to areas, also known as hotspots, that are frequented by key populations, such as venues with a high population of sex workers or men who have sex with men, and this information will have been acquired through a survey.

DiCE is operated through a partnership between the Ministry of Health at the national level and via county governments and donor organizations that provide or support health services in Kenya. Some DiCEs have been established within the compounds of public health facilities, and others operate within the community. A DiCE can also be operated independently by non-government organizations that provide health services, such as LVCT, and such organizations can further sub-contract Community-Based Organisations and, more so, those run by key populations and solely for key population groups.

Jeckonia says that the government and stakeholders within the health sector conduct health surveys to determine the magnitude of disease burdens such as HIV/Aids. The data includes key information such as how different demographics are affected by the disease and can develop a disease profile of the most at-risk or disproportionately affected.

The data has continually shown who the key populations are and that this information guides intervention. Differentiated health provision systems, therefore, recognize these differences and seek to ensure that no one is left behind in health provision.

Within this context, DiCE is specifically designed for key populations, and all services are provided by health providers who are DiCE trained to understand this unique cohort of people, their special needs, their fears and concerns, and overall, to boost an environment that promotes human rights for all. DiCE services are donor-funded and are provided free of charge to all key populations and their clients.

“Key populations are marginalized and underserved. They are also hard to reach through mainstream health infrastructure. DiCE provides differentiated service delivery or a client-centered approach that is designed to respond to the specific or special needs, expectations, and preferences of the various groups of people vulnerable to or living with HIV while reducing unnecessary burden on the health system,” Jeckonia expounds.

She says that key populations may require more frequent health visits than the general population, so they can easily drop in and be served by health providers who can quickly understand their needs. This is essentially the premise of a DiCE—drop in and be served immediately.

Jeckonia says that DiCE broadens service delivery by providing strategically located, friendly, and safe health infrastructure. They also build friendly health system communities for key populations and other vulnerable groups. Peers are also identified and trained to offer outreach services in hotspots such as areas of entertainment like bars and lodgings to help trace those lost and follow up.

For instance, if a person who injects drugs started and stopped HIV treatment and fell off the health system, the individual can be traced through the hotspots where other people who inject drugs are frequently followed by peers who understand this lifestyle. They are also more likely to accept treatment if the information is passed through their peers.

“DiCE is necessary due to the high levels of stigma and discrimination that come with being a member of the key population. There is frequent and alarming targeting of key populations, and they often face violence and threats to their lives. Some have lost their lives. Religion and punitive laws have created a very hostile atmosphere, so such a parallel health system was created to ensure that no one is left behind,” says Jeckonia.

Stressing that “DiCE creates and promotes an environment free of judgment where the key population can freely express themselves and ask for what they need. It is also a space to discuss other issues affecting their daily lives.”

When I accompanied Kijo to S.E.M.A, a covert DiCE located nearly 20 kilometers southeast of Nairobi’s CBD, the services aligned with the Ministry of Health prescribed standards and guidelines, Waithaka, the HIV clinical officer, is also a trained DiCE health provider.

He said that due to the criminalization of their lifestyle, “people like Kijo are hidden and hard to reach with health and behavioral interventions around HIV. In this area, we interact with hundreds of people from the key population group in a month.”

Waithaka says, “Some of their clients also come for services at this DiCE. It is not always about receiving health services; many are here to receive information about how to reduce their risk and vulnerability. Others just want to belong to a community and are here for a listening ear. Others are victims of physical violence and feel safe here.”

“We are flexible, and our hours of operation are adjusted to suit their lifestyle. Increasingly, we are looking at the connection between key populations and pandemics – the HIV pandemic is our primary focus. Still, we have already addressed COVID-19, which is a contact disease, and are now sharing information about the new deadly Mpox 1b strain that is now being transmitted through sexual contact,” he says.

Jeckonia says that key populations’ unique challenges and high contribution to the HIV disease burden make it even more urgent that the government addresses existing challenges. She raises concerns about structural barriers, including punitive laws disproportionately affecting key populations. Meanwhile, she says that stakeholders such as health NGOs have taken it upon themselves to train key populations as paralegals to help each other navigate out of legal problems.

In the Penal Code Act, the primary legislation that defines criminal offenses and their corresponding penalties, sex work is criminalized under sections 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, and 183. If convicted, the offense attracts a jail term of up to three years. Kenya’s High Court, on May 24, 2019, upheld laws criminalizing homosexual acts between consenting adults. These laws have created a hostile environment for the key population community, with human rights organizations estimating that half of LGBTQ+ Kenyans have been assaulted.

My interactions with Waithaka and Kijo at S.E.M.A DiCE sharply put into perspective the dire and urgent need for differentiated health services. A health system that understands that human beings are not monolithic or homogeneous and that every person requires access to a health system that recognizes and effectively responds to these differences is needed.

I understood how the HIV transmission network looks like from a health provider’s perspective and particularly how key populations are intricately linked to the general population. For instance, Kijo is married with children.

“Sex work is just like any other profession. That is why we discourage people from calling us commercial sex workers. When you introduced yourself, I did not hear you call yourself a commercial journalist. Sex work is work, and it is paid work, just like being a journalist, a banker, or a teacher. I get off work and go home to my family,” she says.

“But you then understand that if I do not receive proper health services, I am a risk to my husband and my children because if I get HIV, the chance then of passing it on to my baby is still there. But being a peer educator, I understand more than most people, and I want as many friends, colleagues, and even clients to have the proper information so that we are all safe,” Kijo adds.

Nessie A. has benefitted from peer-to-peer health talks and says they are successful since “you receive information from someone in the same position as you. It is not just about whether this is the right way to use a condom or Prep for cervical cancer screening. It is about the understanding, empathy, and respect that comes with the information. We are like people in a unique clan. We stick together, look out for one another, and even start table banking to prepare for our next chapter. I am aging, my goal is to open a beauty shop.”

Waithaka says that as a client-centered intervention, DiCE is helping identify previously undiagnosed HIV infections among key populations, link and retain them in HIV care and treatment, which has further helped improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy, and this has also helped achieve viral suppression – or in layman’s language, reducing the amount of HIV in the blood to undetectable levels. When you reach undetectable levels in that state, you cannot transmit the virus, which then helps in HIV prevention.

Jeckonia affirms, adding that an estimated 50 percent of men who have sex with men are also married. This means that differentiated service provision helps achieve ambitious HIV targets and promotes structural interventions toward the best possible health outcomes for all. Globally, sexual partners of key populations represent 65 percent of new HIV infections.

She further stresses that the right to health is a fundamental human right guaranteed in the Kenyan Constitution. Kenya’s supreme law states, ‘ Every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to health care services, including reproductive health care.’ Violations of these laws could have detrimental health outcomes and derail Kenya’s HIV response.

Government statistics show the risk is such that HIV prevalence in 2021 was nearly 29.3 percent among female sex workers, 26 percent among male sex workers, 18 percent among men who have sex with men, and 19 percent among people who inject drugs compared with 4.3 percent in the general population. Women aged 15 to 49 years are twice as likely to have HIV vis-a-vis men. Key populations and vulnerable groups significantly contribute to the HIV and STIs burden and, in turn, suffer disproportionately from these diseases.

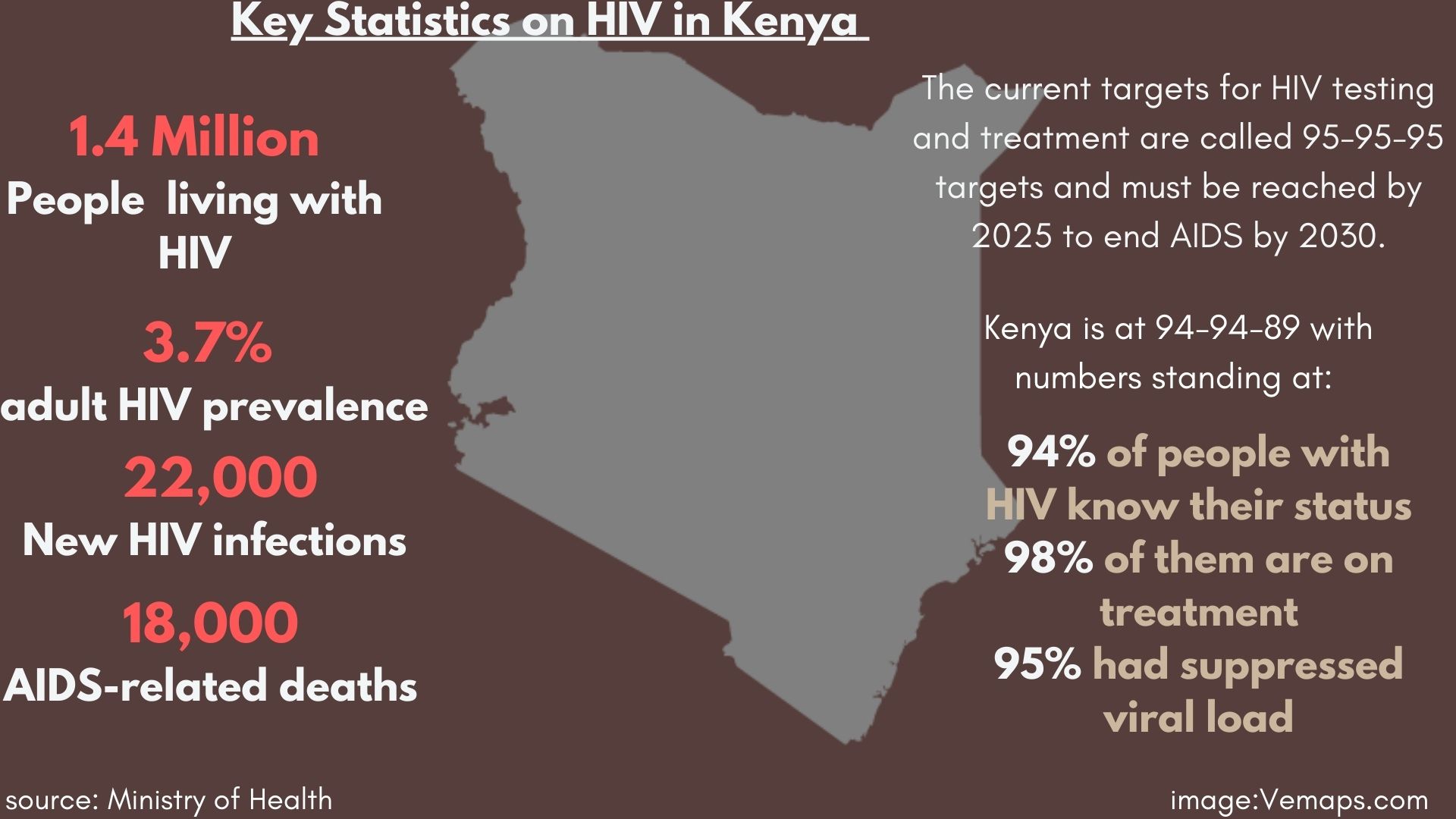

To address the high HIV burden globally, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) established the 95-95-95 targets. For the epidemic to decline and be progressively eradicated, each country must ensure that 95 percent of people living with HIV know their status, 95 percent of people living with HIV who know their status are on antiretroviral therapy, and 95 percent of people living with HIV who are antiretroviral treatment achieve viral suppression.

Waithaka says highly concerning, therefore, is that in 2022, it was estimated that only 7.3 percent of transgender people and 33.7 percent of sex workers were taking HIV treatment in Kenya, as per government statistics. This is much lower than the national average of 94 percent. Due to their elevated risk of exposure, improving health programming for key populations and other vulnerable groups is a pressing issue due to rising numbers, and achieving the 95-95-95 targets within the vital population is indeed a matter of life and death.

Available data by the Partners for Health and Development in Africa shows Kenya estimated a total number of 207,000 female sex workers, 51,000 men who have sex with men, 20,000 people who inject drugs, and 6,000 transgender people. Overall, female sex workers, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and transgender persons congregated at 10,250, 1,729, 401, and 1,202 venues, respectively.

Jeckonia said that this kind of data and mapping helps determine where a DiCE is to be established. Hotspots or areas with very large populations of these vulnerable groups are often the ideal locations. Their existence can then be quickly passed on through word of mouth. While services are provided covertly, DiCE health providers rely on the intricate network of key populations and the peer-to-peer model to provide services.

As she navigates a hotspot for sex workers in the early hours of the evening to provide HIV and cervical cancer screening-related information and distribute free condoms, I have a front-row seat into Kijo’s profession. In between, she tells me about her life at home and her grandmother, who is still alive and well. Her grandmother has made peace with her chosen path in life. Her grandmother came along when she attended training in Mombasa in June 2024. Perhaps she should close a chapter with her departed daughter as she continues another with her granddaughter.

Kijo is in her element and content. For her, it is just any other day in the office and a good day today. We interact with 16 young women in various bars and lodging areas before I am ready to call it a night. Through this ‘tell-a-friend-to-tell-a-friend’ peer-to-peer model, she says that word quickly goes around within their networks, using in-bred codes that only these groups understand to maintain the high level of privacy that goes with the DiCE model.

Female sex workers who test HIV positive are linked to care and treatment within one to two days. They are also provided with information about antiretroviral therapy support groups within the keypopulation community and absorbed into existing support systems, which produce positive health outcomes, such as adherence to treatment. But most importantly, she aims at linking all sex workers to a DiCE.

Jeckonia says DiCE takes into account the lifestyle patterns of key populations and can open and close as early or as late as necessary. Services are provided through language-sensitive practices and a culture of non-discrimination. DiCE health providers are specially trained to have an appropriate attitude and approach that is in harmony with the objectives of differentiated service provision.

Nonetheless, she says that DiCE faces sustainability issues despite its keyrole in delivering services for hard-to-reach populations. For instance, even though key populations account for 70% of new HIV infections globally, only a small percentage of global HIV funding is spent to address their HIV prevention, treatment, and care needs. Funds are not enough to support differentiated service provision.;

The Ministry of Health is conducting the 2024 Bio-Behavioral Survey in select counties to provide information on behavioral and HIV seroprevalence information among men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers (FSW), and people who inject drugs (PWID).

This will, in turn, inform HIV program planning among key populations as per the universal health coverage interventions. Universal coverage is expected to phase out differentiated service provision, as its concept of universal access is predicated on health equity for all.

Without decriminalizing key populations and removing structural barriers to health services, fears are rife that these vulnerable groups will fall entirely out of the health system, erasing Kenya’s successful footprint on the road to 95-95-95.