By Joyce Chimbi

Nairobi, Kenya: Phena Nyamatu stares ahead, apprehensive, speaking in hashed tones as if the horrid past were only a bad nightmare—afraid that saying the words out loud would turn a bad dream buried back in February 2019 into a painful reality.

She is reaching for memories of her niece, a bouncing baby girl whose only anomaly was appearing to have been born with teeth. She explained how her highly alarmed family turned to the designated traditional birth attendant (TBA) in Mombasa Raha, an informal settlement in Nairobi’s Mathare Area.

The TBA’s only qualification was successfully self-delivering her two children over three decades ago. “She said that the teeth must be removed, and they were. But my sister and her baby still died within the same year,” she says.

Cephas ‘Mogaka’ Nyamwamu, a Community Health Promoter (CHP), hints at what could have caused the untimely death of the baby girl: “Those white things that look like teeth are simply plastic teeth and are nothing to worry about. However, in some informal settlements, TBA’s word is the law.

“So affected babies are left with wounds in their mouth and whatever the mother has in her blood, be it HIV, Syphilis, Hepatitis B and C, will go to the baby during breastfeeding,” he expounds.

I am traversing Nairobi’s informal settlements to uncover the role of digitally enabled CHPs in addressing multiple childhood diseases, an overreliance on TBAs, and the minefield of myths, misconceptions, and superstitions surrounding newborns derailing Kenya’s efforts to eliminate preventable infant and child mortality.

A focus on the extent and magnitude of these issues, their contribution to child health, and what CHPs are doing to reverse alarming trends in child mortality – government statistics paint a worrisome picture.

According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2023, the child mortality rate is 41 deaths per 1,000 live births, significantly higher than the international target of 25 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Worse still, neonatal mortality declined by only one percent from 22 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2014 to 21 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2022. Kenya is grossly off-track Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, which aims to reduce neonatal mortality rates to 12 per 1,000 live births by 2030.

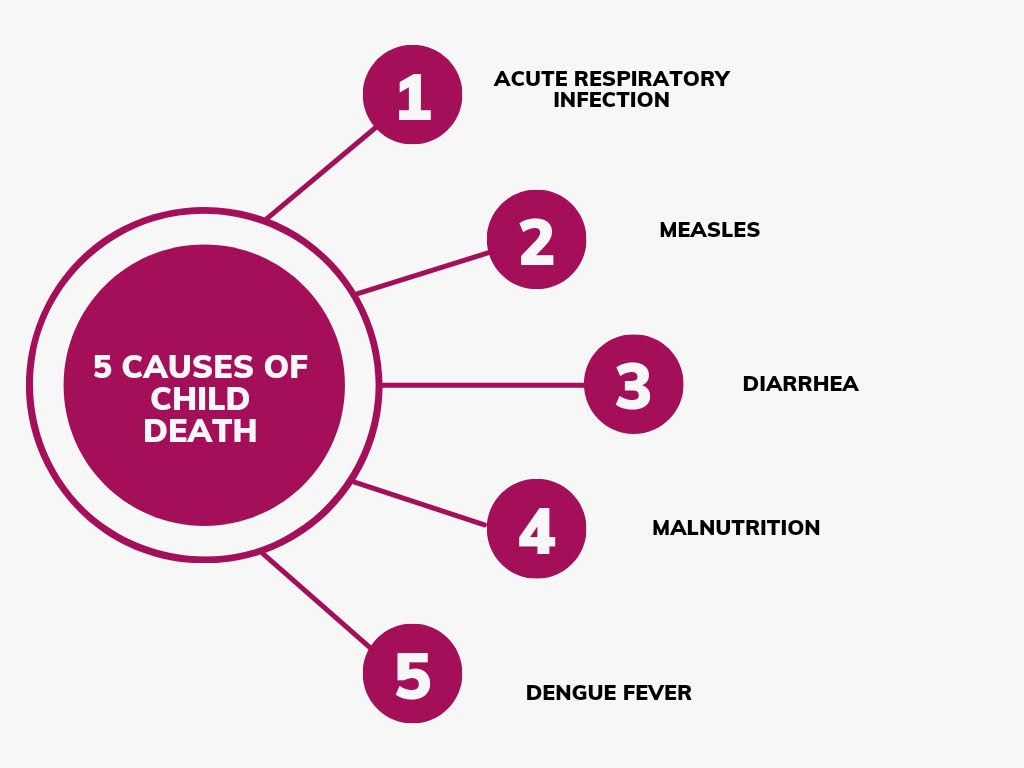

Across urban informal settlements, children’s vulnerability to killer diseases such as polio, cholera, diarrhea, and vomiting is heightened by a lack of sanitation services, running water, and sewage systems, and a largely poor resident living on an income of less than two dollars (KES 200) a day.

Other factors, such as harmful religious and spiritual beliefs and a prevailing preference for traditional medicine, have worsened an already bad situation.

“CHPs are on a mission to seek and find what ails young children. Is it cholera, polio, religious beliefs, or fear of witchcraft, hence a strong belief in traditional medicine, that is causing high child deaths? We do not just look for symptoms but causes, too, to help us offer effective solutions,” Nyamwamu expounds.

Regarding disease outbreaks, Kibera is of particular concern as it is the largest urban informal settlement in Africa and one of the largest in the world. Kibera is a vibrant, densely populated area in Nairobi, where an estimated 250,000 people live in an area of just 2.5 kilometers.

The entire settlement is divided into 13 villages, and the living conditions are deplorable. They are so dire that the average size of a shack in Kibera is 12ft x 12ft, built with mud walls, a corrugated tin roof, and a dirt or concrete floor. These shacks often house up to 8 or more people, with many sleeping on the floor.

“A disease outbreak like cholera or diarrhea could kill many children in just a few days. Polio itself spreads as fast as Ebola. Before, we could only detect a disease outbreak after many children had presented similar symptoms and died. Today, we have a digital solution helping CHPs create a health profile of children, enabling us to detect signs of trouble in good time,” says Irene Onkoba, CPH based in Darajani, Kibera.

Onkoba is holding the solution in her hands. It is the Electronic Community Health Information System (eCHIS-Kenya) under the Ministry of Health (MoH). This aligns with the Kenya Community Health Policy, which requires digitally enabled CHPs to use the eCHIS platform to manage their caseloads.

The app is embedded in government-provided smartphones to phase out old reporting tools that were time-consuming, cumbersome, prone to error, damage, and loss, and whose data was hard to verify. The digital system is user-friendly, and information can be easily and efficiently aggregated at the local, county, and national levels for expeditious decision-making.

Previously, CHPs used reporting tools provided by the Ministry: MoH 513, the Household Registry, and MoH 514, the Service Delivery Logbook. eCHIS enables quick detection of health-related problems such as disease outbreaks and facilitates expeditious response.

“MoH is professionalizing CHPs to ensure that we are trained, equipped with digital tools and basic medicine for everyday use, supervised, and paid,” says Onkoba.

She says the transition to the digital platform has had its share of challenges, as many CHPs have a modest academic background. However, the national and county governments continue to conduct comprehensive training exercises to facilitate a smooth transition.

“All CHPs are now under the supervision of a Community Health Assistant (CHA). CHAs provide us with technical support and guidance. The only challenge here is that they are overwhelmed by the many CHPs under their supervision. For instance, we have one CHA in Kibera,” she says.

Onkoba says eCHIS has provided a robust disease monitoring and surveillance system, and more so about child killers such as polio and cholera. Poliomyelitis’ most severe symptom is paralysis, leading to permanent disability, and in five to 10 percent of all polio cases – death as breathing muscles become immobilized.

eCHIS came at the right time due to polio and cholera outbreaks that threatened to reverse gains in child health throughout 2023. CHPs used the platform to ensure that the diseases were under control.

“We did our usual door-to-door and collected information in each household. When you enter the information in eCHIS, by the time you leave your designated area, the system will have shown that you will be informed if all is well and if something is wrong. It will give you a summary of what is happening in these households and you can immediately detect the presence of a disease because the app will tell you,” Nyamwamu expounds.

Josphat Kinuthia, a medical expert at Nairobi City County Department of Health, says CHPs effectively submitted immediate health reports for action by county health departments and the national government. The country was on high alert when polio was detected in Kenyan refugee children in 2023. MoH activated a vigorous and thorough mass polio vaccination campaign conducted by CHPs in three phases.

“We are assigned 33 to 100 households each. We visited these households and ensured all children under five years received the polio doses. Families that refused to immunize their children were reported to the area Chief. Where necessary, the cases were reported to the area Officer Commanding a Police Station (OCS),” Onkoba expounds.

She says that Polio is a public health issue and “placing your child and other children at risk is an offense. This is the work that clinicians and nurses cannot do. They deal with health problems inside the hospitals, but we deal with similar health problems within the community.”

None of the primary health units, including all Beyond Zero Clinics, Kibra Health Center, Kayole 1 Sub County Health Center, Dandora 1 Health Center, and Mathare North Health Center, which serve Nairobi’s informal settlement catchment area, recorded any cases of poliomyelitis.

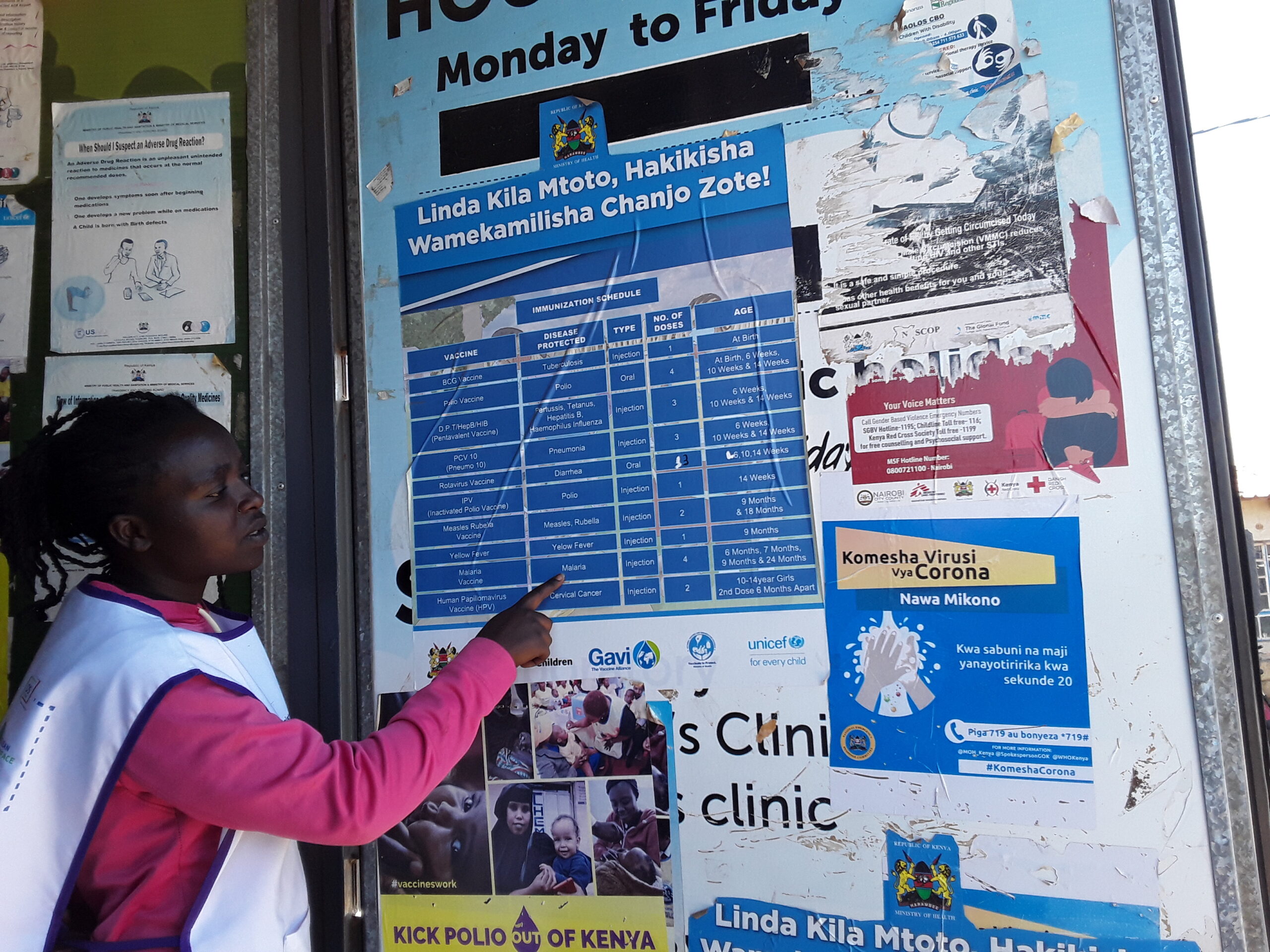

The Beyond Zero Clinic, located in the heart of Kibera informal settlements, is an outstanding example of collaboration between a primary health unit and digitally enabled CHWs. The Clinic boasts an optimum routine child immunization rate supported by a robust outreach program conducted by CHWs attached to the facility. The facility has surpassed all immunization targets for all child vaccines.

In 2023, this primary health unit immunized all targeted children in its catchment area and additional children from surrounding areas and recorded no cases of cholera and measles and zero deaths from diarrhea and pneumonia, which are a leading cause of death among children under the age of five. The clinic did not record any vaccine-preventable death in 2023, the first year the facility worked hand in hand with digitally enabled CHWs. Thus far, the Clinic has maintained the gains accrued in 2023.

Polio was not the only serious child health concern. Towards the end of March 2023, MoH confirmed that at least 7,800 cholera cases and 122 deaths were recorded across the country. These cases were concentrated in four counties and more so, Nairobi.

In February 2023, the Ministry of Health prioritized and targeted all four counties with the first-of-its-kind Oral Cholera Vaccination drive to control the cholera outbreak and end the disease.

The 10-day vaccination campaign targeted at least 2.2 million people and was entirely conducted by CHPs. They moved door-to-door, using eCHIS to determine high-risk areas and track immunization progress. The Division of Disease Surveillance and Response in Kenya’s Ministry of Health says that 99.2 percent of the target population was ultimately reached.

“Since the first cholera case in 1971, the country continues to face cholera outbreaks. We had a severe outbreak in 2015. The outbreak fizzled out in 2016. Cholera returned in 2017 through 2019. In 2020, we had 711 cases and 13 deaths. We attribute the successful fight against cholera in 2021 to CHPs’ work on the ground. We had no deaths from cholera in 2021,” says Kinuthia.

Further, “In 2022 and 2023, cholera returned, and it was a severe outbreak due to the severe prolonged drought, but we worked with CHPs to contain the problem through water and sanitation interventions and the cholera oral vaccine.

“Doctors, nurses, and clinicians stay in the health facility; CHPs inform the community about these diseases and what they can do to be safe. If you were to remove CHPs from the health equation, it would be a health catastrophe,” Kinuthia expounds.

Nyamwamu says monitoring and responding to disease outbreaks is as important as addressing factors that keep children from accessing quality health care or even harmful practices such as plastic teeth removal that heighten a child’s vulnerability to infections. Digital platforms, he says, are helping close these gaps and loopholes.

“Since we started walking around with these gadgets, I have noticed that the community’s attitude towards us is changing for the better. CHPs are not the most educated and we live with the community so they can easily look at us as their equal. But now they see us in a uniform, a bag from MoH, and a smartphone. I am feeling increasingly respected as an authority in community health, and I believe that my health messages are being better received,” he notes.

In addition to eCHIS, CHPs and their supervisors have access to the Integrated Management of Neonates and Child Illnesses digital system, which enables them to diagnose child diseases at home.

“You enter a child’s information and the symptoms they are presenting into the integrated system and it will give you a diagnosis,” he expounds.

Kinuthia says CHPs visit newborns within 48 hours of being discharged, raising awareness of health-promoting behavior such as the importance of exclusive breastfeeding while also conducting growth monitoring.

“It is true. We had a case where the Chief came to my house because I refused to allow a CHW to see my newborn baby. The church does not allow a baby to be seen by outsiders before 40 days are over. The CHW was shocked to see my baby’s yellow skin, and we were forced to go to the hospital. The baby was very sick, and we did not know because he was quiet and not crying. He was kept in the hospital for ten days. David is now three years old, and he would not have survived had we hidden him for 40 days. He was born with a problem, and the doctors fixed it because the CHW insisted that we go to the hospital,” says Sandra Juma, Darajani, Kibera.

In the same community, Brian Wekesa talks about how a CHW saved his one-year-old son as the mother refused to take the child to the hospital “because we do have this belief that somebody can send wounds inside a baby’s mouth, so traditional herbs should be the first option to remove the evil spirit. My mother had already sent us a liquid herb, but it was not working. The baby had sores in the mouth and could not breastfeed or eat due to the pain. A CHW, who is also a neighbor, found out and gathered a few neighbors, and they took the baby to the hospital by force.”

They further stated that “my son slept at the hospital for two nights. I was born in this area, and we used to have many cases of children dying from diarrhea and vomiting; sometimes, a baby would sleep and not wake up, and we would say it was witchcraft. Then we started having CHWs coming to our houses many times a week, and I used to have a low opinion of them, thinking that they were idle. But my experience has taught me that children are safe when CHWs visit them at the house because they can detect problems before a child dies from something that could have been prevented.”

Nyamatu, whose niece had plastic teeth that were removed, leading to her death, says that the death worsened conditions at home, “we were in denial and believed that we had been cursed. The birth of my son two years ago put us on the path of healing. A CHW would come to our house, where I lived with my mother and sisters, to see my baby. She connected us with a counselor, and we have accepted the past and are moving on.”

She says that without CHWs, “many babies would be suffering from ignorant family members. Babies would be unsafe from the same people who love them the most because we are still trying to respect our roots and, in some cases, these roots can be dangerous to children.”

The first community health worker entered Kenya’s community in 1988. After years of relentless dedication to operating noninstitutionalized and unrecognized by the health system they serve, a country-wide mapping of CHPs and Community Health Assistants started in early 2023. The aim was to ensure that all 100,000 CHPs were integrated within the public Primary Health Units in their areas of operation. The exercise revealed that there are 7,000 CHPs in Nairobi alone.

The World Health Organization (WHO) places significant importance on CHPs as they are the foundation of the health sector, especially in light of insufficient health workers in resource-strapped settings amidst a concerning rise in climate-induced health outbreaks such as cholera.

Kenya is still reeling from the most severe drought in the last 40 years. As climate change pushes the country to the frontlines of disease outbreaks while worsening the magnitude of endemic diseases, such as malaria, cracks in the health sector are increasingly glaring. At best, Kenya’s patient-doctor-to-patient ratio is 1:17,000, which is against WHO’s recommendation of 1:600.

The country’s health service sector, especially among the poor and vulnerable in informal and semi-formal urban areas, is propped up by the relentless volunteering spirit, passion, and dedication of 100,000 CHWs across 47 counties.

“We see what the doctors and nurses cannot and will not see. The fears of and beliefs in witchcraft and, bad omens have led to deep-rooted harmful practices such as rubbing a newborn’s mouth with ‘protective’ herbs and feeding them herbs in powder form even before they are six months old. We are focused on improving proper health-seeking behaviors,” Nyamwamu expounds.

Religious sects such as Legio Maria, Akorino, and Nomiya Church present a unique set of challenges. Ardent followers still largely favor no contact with health facilities, significantly increasing the number of zero-dose children or children who do not receive a single dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis-containing vaccines.

Kinuthia – the County medical expert, says zero-dose children account for nearly half of all vaccine-preventable deaths from illnesses such as diarrhea and pneumonia. Some churches, for instance, require that newborns be kept behind closed doors for 40 days, and many of them will eventually start nursery school without a single dose of vaccination. Children face the highest risk of death in the first 28 days – the neonatal period. However, some, like the Nomiya Church, allow parents to arrange for their child to be vaccinated in the house.

Nyamwamu says CHPs are not only working diligently to reach zero-dose children, but they are also at the heart of Kenya’s escalated efforts to prevent the triple threat of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, Syphilis, and Hepatitis by ensuring that all pregnant women within their radius complete at least four antenatal visits.

Alarming 2022 data by the National Syndemic Diseases Control Council signaled the return of syphilis. Four out of 10 pregnant women who sought care tested positive for syphilis. Nairobi County recorded the highest number of women with syphilis.

Similarly, Kinuthia explains that Kenya remains vigilant against Hepatitis B as it is one of 33 African countries whose prevalence is more than 1 percent among children younger than five.

Along with smartphones, CHPs have additional tools such as a glucometer, weighing scale for community-centered baby growth monitoring, thermometer, cord clamps, a nipper to tie the umbilical cord to stop blood flow from the placenta to the fetus during an emergency delivery outside a health facility, a torch, and a tea thermos.

A community health assistant supervises their work, and for the first time, they are on a modest but much-needed stipend of USD26 (Kes 3,500). Although eCHIS is highly user-friendly, the digital transition is not without its challenges. To submit the report, the smartphone must be connected to the internet, and it is upon CHPs to facilitate internet connectivity despite only receiving a modest monthly incentive.

“In the beginning, the app would freeze, but it was mostly due to user error. With continued training, we face minimal technical challenges,” says Onkoba.

Despite being digitally enabled, CHPs still walk door to door, urging the ministry to provide them with motorbikes to facilitate movement. Nevertheless, they remain vigilant, one doorstep at a time, keeping diseases at bay.