By Lilian Museka

Kenyans are set to start enjoying Universal Health Coverage (UHC) following the announcement by President Uhuru Kenyatta in October to launch a pilot programme in December 2018.

The programme which will coincide with World Aids Day will see more than 3 million Kenyans from four Counties, namely Kisumu, Isiolo, Nyeri and Machakos benefit in the first phase, which is expected to last one year.

After registration is done, patients will be treated for free, both outpatient and inpatient including referrals.

The success of the pilot project will clear the way for the national roll out that will mark the beginning of a new era in the public health sector, with the objective of achieving the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 3 as adopted in September 2015 to ensure “healthy lives and promote well being at all ages.”

During a meeting with the UHC Intergovernmental committee in October, Health Cabinet Secretary Sicily Kariuki said the pilot project will cost the government up to Ksh. 3.17 billion

The country’s vision 2030 is committed to be a competitive and prosperous nation in offering quality life for all by 2030. Investing in a quality delivery system is enshrined in the vision.

The government has since made considerable progress by importing 100 doctors from Cuba in June to curb on the current shortage of healthcare workers. However, the number is still on the lower side compared to the daily patients visiting hospitals.

The 2015 Kenya Health Workforce report titled The Status of Health Care Professionals, prepared by the Ministry of Health and America’s Emory University showed that Kenya had only 2,089 special doctors, 5,660 medical doctors, with 387 specializing in gynecology and experts in general surgery, at 338

Data from Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Board shows that the country has a shortage of 34,445, with only 4,344 doctors having been registered by the board to serve about 38 million people in public centers.

World Health organization (WHO) recommends a ratio of 44-45 nurses, physicians and doctors to take care of 10,000 patients.

“When you visit public hospitals, you will find long queues of patients waiting to be attended to by either a nurse or a doctor. Sometimes you find the care givers are overwhelmed during emergencies. The situation is so dire that some cases requiring urgent attention are given later appointments running even into a year. If we can have more care givers, this problem can fairly be solved, “says Jinit Shah, director at Ujuzi Fursa Africa.

Shah notes that most people are turned away from medical schools for lack of minimum qualifications, contributing to the big shortage. According to the Kenya medical Training College (KMTC) entry requirements, one must have attained a C plain to qualify for a diploma course and a C- (minus) for a certificate course in medicine. This, he says has shut out many prospective Kenyans who have a passion for care giving.

“This is why we set up Ujuzi Fursa Africa, to train and certify professional caregivers to bridge the gap of health care givers, who can specifically go out and attend to our target patients, who are the elderly in the community, “ he says

The organization offers home based care giving by connecting the trained and certified caregivers through an online platform where clients (families of elderly patients) can access them for services at home.

“We publicly display the certified caregivers on the online platform on our website where clients can read about their qualifications and contacts. Depending on the need, the client will then contact us and we will send the caregiver to them, to attend to the client. This is purely home based care giving service where patients are taken care in the comfort of their homes,” he says adding that “In case of any medication, we partner with such hospitals as South B Hospital, Nairobi West Hospital, and Aga khan.”

Shah says most of their clients are hospital discharges that require close monitoring, either with fractures or chronic diseases like cancer. He adds that, “Depending on the situation, the caregiver can attend to client for a day or for up to 3 months. The care ranges from an hour to three hours in a day. Services offered include feeding, hand holding for pre and post appointment, bathing, toilet assistance, bed making, grooming, walking, exercising, oral hygiene, paper work filing, companionship, managing medication and perennial care which may include physiotherapy among others.”

The organization charges range from a day to a month. In a day they will charge a maximum of Ksh. 1,000 while in a month a maximum of upto Ksh 24,000 depending on the needs of the client.

Before taking a client, they will do a risk assessment to ascertain the needs of the patients, after which they will send three caregivers and the family of the patient is given an opportunity to choose their preference out of the three.

“The advantage of this kind of service is that we do matchmaking to ensure that the patient is satisfied with the service provider. We go with their preference unlike at public hospital where you may not have much choice,” Shah says.

So far, Ujuzi Fursa Africa has attended to 45 cases since the inception of the programme early this year and most of their target is upper and middle class. “We have patients from Langata, Dagoretti, Uthiru, Lavington, Kangemi, Nairobi West and Westlands. We plan to roll it out to the rest of Nairobi and the whole country.” Says Shah.

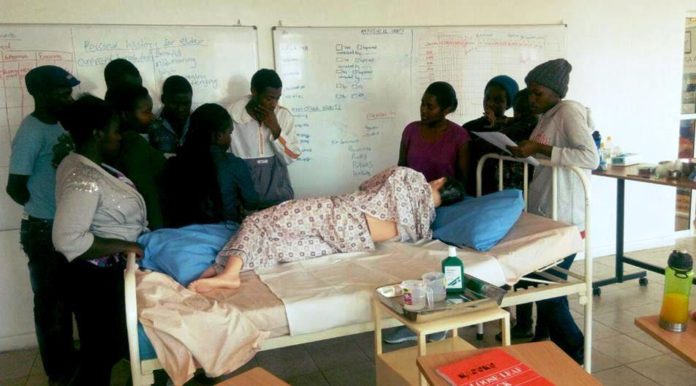

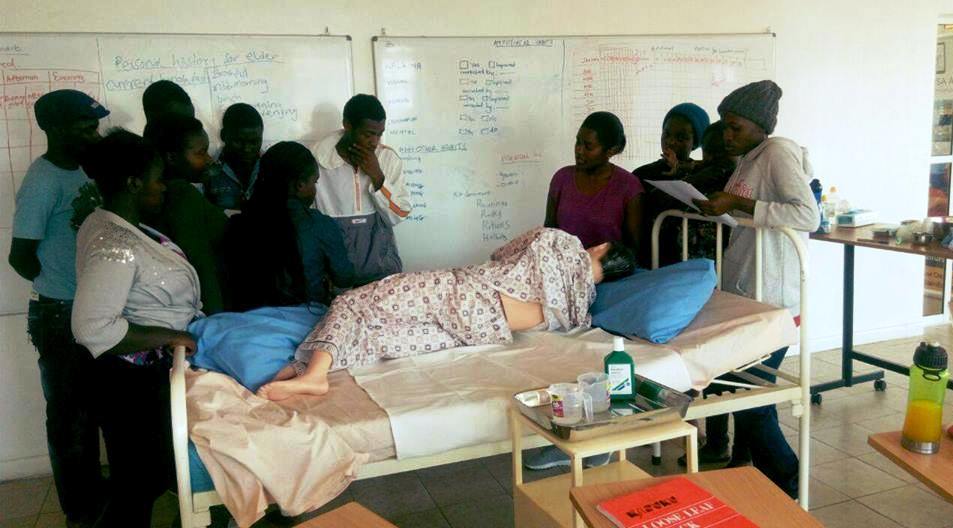

The care givers are trained at Ujuzi, which has a school based programme, where trainees attend classes for 11 weeks and they pay Ksh 30,000. The school is certified by The National Industrial Training Authority (NITA), and the training curricula formulated in Singapore and CPR First Aid Certification”.

The course covers classroom training, online learning and a clinical internship placement. “ The learners use video materials and blend it with dummies for practical . “After this we send them for internship to Guru Nanak and Getrude hospitals for four weeks. Once they are done with internship, they come back for certification and graduation after which the learner is free to proceed for further specialized studies or take up an offer with us as a community healthcare giver or even get a job ,” he adds.

The organization has so far 9 trainings with two classes for each training, one running from 8am – 1.30pm while the other from 2pm – 7pm.

Shah says the social enterprise has lowered the minimum entry level to grade D (plain) in form four. This he says helps in accommodating many people who have been turned away from medical school for not attaining the minimum grade. He however quickly adds that one must be good at English where they give an entry level exam.

So far, the organization has trained 90 care givers, 70 of which are working in different places while retaining 20 as community health care givers.

“We mostly target the youth between 18-24 years coming from poor backgrounds that either didn’t achieve the entry levels to medical schools or are unable to raise the high education fees that the medicine schools charge. The Ksh 30,000 is spread over the whole course to enable them be able to pay. We have also offered scholarships to six students that we saw potential in them but they could not afford to pay the amount,” adds Shah.

The organization advertises the school through public meetings where they go to communities, with invitation from elders like chiefs or members of county assemblies with the aim of winning over the youth to enroll for the training.

But what really motivated the director to set up such a social enterprise that is not common among Kenyans? “My grandmother fell ill 10 years ago and after a long battle of treatment with different doctors at various hospitals, we opted for a home caregiver, who was a nurse. She was however very expensive and would not want to offer such services as psychotherapy, toileting, grooming and even feeding her. This angered me and I started searching for options. I got to learn about the home care giving method in Japan, and this is how I borrowed the idea and started implementing it,” Shah answers.

The Japanese government has promoted home healthcare, since 1989 when the Ten Year Strategy for Promoting Health and Welfare of the aged (Gold Plan) was enacted, setting a flow for switching from care at facilities to care at home. In 1992, the Medical Care Act was revised to position homes as places for providing health care.

“The programme has worked so well in Japan that it has also improved relationship between grandparents and grandchildren,” says Shah.

An article on systematic review of grandparents’ influence on grandchildren in Japan published on 2017 and written by Stephanie Chamers, Neneh Dewar, Andrew Radley and Fiona Dobbie suggests that grandparents have an adverse impact on their grandchildren. This means they can heavily influence them negatively or positively.

“This is the kind of programme we are trying to implement in Kenya and we are asking people not to dump their elderly at villages as there is no proper care for them but allow care givers to attend to them as they even bond with the grandchildren,” says Shah

Culturally, Kenyans take their elderly to the village and prefer extended families at home taking care of them. “We are hopeful that this concept will work so that the elderly are given proper and deserving care,” he says.