By Philomena Gitau

East Coast Fever is a tick-borne cattle disease that kills up to 80% of calves every year. An animal dies within 14-30 days after the tick bite. The most effective way to control the disease is an expensive vaccine known as East Coast Fever (ECF) vaccination, which costs between 5-6 USD per animal, giving almost 100% protection.

Since 2003, the ECF vaccine is distributed on a commercial basis, and the Maasai pastoralists were very keen to pay for it because it dramatically improved their lives. Unfortunately, since 2012, two international organizations the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and the Global Alliance for Livestock Veterinary Medicine (GALV med) stopped producing the vaccine which sparked the illegal sale of the ECF vaccine in Tanzania by other companies and is still going on.

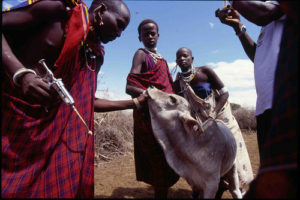

By the year 2015, more than 90, 000 cattle died, mostly in Monduli and Simanjiro districts in Northern Tanzania. These deaths were, and are still being caused by dishonest ECF vaccinations involving the injection of half (0.5cc) of the required vaccine dose of 1.0cc. The cattle die because 0.5cc of the vaccine does not give protection against the disease.

“The fraud is perpetrated by people who are to make money at the expense of the Maasai pastoralists”, said Dr. B. Di Giulio, a veterinary and the president of the Maasai Emergency Association based in Rome, Italy. He said this during a Maasai Press Conference in Nairobi, Kenya, where some of the Maasai pastoralists’ representatives were present.

The ECF vaccine production is a long and cumbersome process that lasts between 16-18 months. Usually, it is difficult to foresee the number of vaccine does which will be produced. In 2006, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) produced its second and last ECF vaccine of 1.2 million does, which lasted until the end of 2014. The vaccine production involves the use of several thousands of infected ticks. Presently, the only ECF vaccine producer is the revamped (2010) Centre for Tick and Tick-Borne Disease (CTTBD), an African Union project based in Malawi. CTTBD is a trust. However, it’s overreliance on producing ECF vaccines raises questions about its sustainability, and therefore the long-term availability of the vaccine. Following this fact, pastoralists want ILRI to continue producing ECF as it worked efficiently than the current one being distributed.

Massai Pastoralists and their representatives say that both ILRI and GALmed, together with some of their donors, have refused to take responsibility and in spite of several direct requests through emails and calls, the two organizations are still adamant to meet them.

In October 2016, a group of Maasai Delegates visited Europe so as to meet the donors and pass their grievances but the visit bore no fruits as the donors never met them, therefore, no action was and hasn’t been taken so far. “Maasai fully depend on cattle for almost everything, from food, shelter, clothing, schooling etc., and so when cattle die, Maasai people die”, said Daniel Somoire, the secretary of the Maasai Emergency Association, Kenya.

“Some of the vaccinators who are sent to administer the vaccine go with 80 tags while the ECF they have is only for 40 cattle, meaning they vaccinate the cattle with half the dose of ECF”, said Tanzania Emergency Association secretary Isaac Sanango. “There’s no difference between having the vaccine in half doses and not having it at all because cattle are still dying either way”, he concluded.