By Lenah Bosibori (Kenya), Emmanuel Ngabo (Rwanda), Yanne Mbiyavanga (DRC), Daniel Samson (Tanzania), Sarah Biryomumaisho (Uganda) and Rénovat Ndabashinze (Burundi)

Across East Africa, climate change is no longer a distant threat but a daily crisis reshaping lives. From the rising waters of Lake Tanganyika swallowing farmland in Burundi to unpredictable rainfall devastating crops in Rwanda and Tanzania, extreme weather is fueling food insecurity and economic strain. As food inflation increases and protests erupt in DRC and Kenya over the high cost of living, the effects of a changing climate are becoming impossible to ignore. Farmers, policymakers, and communities across the region are grappling with a harsh new reality: how to adapt and survive in an environment that no longer follows familiar patterns.

East Africa, home to over 331 million people, is bound together by rich cultural and linguistic ties. However, the region faces a growing crisis beyond these shared traditions: climate change. Tanzania, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are grappling with its intensifying effects—rising temperatures, erratic weather patterns, and food insecurity.

These impacts are already disrupting lives. Farmers are losing their harvests to floods and droughts, inflation is driving food prices beyond reach, and communities are struggling to adapt. Climate change is no longer a distant threat but a daily reality reshaping economies and livelihoods across the region.

On May 21, 2024, peaceful protests erupted in Kinshasa over the soaring cost of living. A year earlier, in 2023, similar frustrations had fueled deadly demonstrations in Kenya. While these protests may appear purely political, they are deeply linked to food insecurity worsened by extreme weather. Unpredictable rainfall, prolonged droughts, and floods have slashed agricultural yields, driving inflation and making staple foods unaffordable.

In 2024, food inflation across East Africa reflected this crisis, with most countries—except Uganda—recording sharp price increases.

Lost Livelihoods

In Rumonge, Burundi, farmers are in despair as the waters of Lake Tanganyika flood their farmlands. “I’ve lost almost everything. Look at all these hectares. These were oil palm plantations. But now, everything has been flooded, destroyed by the water,” says Joseph, a sixty-year-old oil palm farmer, as he stares at the grounds he once eked a living out of.

Father of six, he indicates that due to these floods, his losses are incalculable: “In any case, for a harvest season, I couldn’t miss out on 100 million Burundian Francs (equivalent to $33,772, using the official rate). Now I can only hope for 5 million Burundian Francs ($1,688) for the parts that aren’t completely flooded,” Joseph stated.

Today, he says that it is difficult for him to provide for the food needs of his offspring. “You also have to know that in these oil palm plantations, we could grow beans, sweet potatoes, etc. Now, there is only water,” he adds.

Rising water levels are not unique to Lake Tanganyika. A study of East African lakes found that surface areas expanded at 205 lakes between 2000 and 2023, primarily due to increased rainfall. Lake Victoria, the world’s second-largest freshwater lake, has also seen fluctuating levels, disrupting fisheries and lakeside communities.

At Kibirizi market, one of the busiest in Karongi District, Western Province of Rwanda, farmers are struggling to survive with the rapidly rising cost of food. Maniriho Jean Bosco, a father of four who lives in Gitesi, says food prices have increased in the last five years, but his income hasn’t.

He also decries the unpredictable weather patterns. “It no longer rains as it used to; times have changed. It rains in September, or it rains late, and then we seed in October. Nowadays, the rains are irregular and damaging.”

After buying onion seeds for about $35 and leasing land for over $71, temperatures may rise instead of rain coming as expected. “It is a loss,” he stated. He adds that seeds are more expensive than they were, adding to the pressure. “A can of green pepper seed now costs up to $6; when you harvest a kilo, it costs $0.14 or $0.07 in the market. Some farmers have left their crops in the fields as they bought the seeds at a high price, and there is no market.”

Like most East African economies, Tanzania relies heavily on agriculture. Climate change is disrupting this sector, threatening the country’s food supply and economic stability. When the agricultural season began in November 2024, Mwichande Mnyang’anyi, a 66-year-old farmer in Bahi District, Dodoma Region, was optimistic. “The rains started well,” he recalls. “I thought we were going to have a good season.”

But his hopes faded when the rains stopped in February. “It’s getting harder. There has been no rain since then,” he says. Mnyang’anyi now worries about feeding his family. His rice yields, which typically produce at least 25 bags (100 kg each) per hectare, are expected to drop to just 5 or 6 bags this year due to drought and pest infestations. Across Tanzania, thousands of farming households face similar struggles. With unreliable rainfall, reduced harvests, and rising production costs, food insecurity is worsening.

Across the border in Kongo Central Province in DRC, climate change manifests through the emergence of aphids– a tiny sap-sucking insect. “These aphids do not resist when it rains, but when it does not rain, it creates conditions for aphid infestation. They can reduce yield by 30 to 70%,” Martin Kimvuta, Kwilu-Ngongo Sugar Company’s agronomic research manager, expounded. With its thousands of hectares of farmlands producing over 80 million tonnes of sugar, climate change is a threat to the sugar company, which is DRC’s only sugar producer.

“In extreme cases, infestation can cause mortality of young canes with impact on field productivity,” Kimvuta further explained. In addition, sugarcane needs water to grow; a lack of it therefore adds to the problem.

Food Insecurity in East Africa

In DRC, an October 2024 Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) analysis found that 25.6 million people—approximately 22% of the country’s analyzed population of 116 million—are in crisis or emergency levels of acute food insecurity.

The situation is similarly dire across East Africa: In Kenya, 895,000 people faced acute food insecurity in 2024, while in Uganda, prolonged drought has affected over 797,000 people. Chronic food insecurity across the region demands urgent interventions spanning short-, medium-, and long-term solutions.

“There are significant impacts of climate change on Uganda’s food security; the increasing temperatures reducing the suitability of many areas of production of some crops,” the Food and Agriculture Organisation said in a statement.

Factors Exacerbating Climate Change

When Serina, a resident of Bunyangabu District in Uganda, secured 10 acres of agricultural land in Fort Portal, she thought her financial and food burdens would end. This vision of earning enough money to pay school fees for her children and produce enough food for them would reduce financial stress. The area she acquired for cultivation was a “mini-forest” as she describes it, with different kinds of vegetation including several trees.

“After the first three seasons, I started making losses. At first, I did not need fertilizer; the land was fertile, and all plants grew without additives. However, I would spend at least $817 on fertilizer alone for the gardens and an additional $108 per acre each season for 10 acres,” Serina explained. “Imagine, I needed fertilizers to grow beans and Irish potatoes. That was unheard of,” she continued. “I have no more money to spend,” said Serina. Now, over ten seasons later, she abandoned the gardens and returned home, where she cleared her farm, turned it into a potato garden and sold off all her cows.

Where a sack of potatoes sold for $43 five years ago when Serina started commercial agriculture, it’s now doubled to $89 in some villages. These steep price increases, coupled with farmers abandoning the trade due to drought, result in higher food prices beyond the income of many households.

According to the Uganda Ministry of Water and Environment, on average, 122,000 ha (six and a half times the size of Kampala) of forest is lost every year.

“This unprecedented loss of forests is among the major local causes of climate change in Uganda. Deforestation contributes to climate change by releasing carbon dioxide, reducing the Earth’s ability to absorb CO₂, disrupting local climates, and triggering destructive feedback loops,” says Dr. Emmanuel Zziwa, the assistant team leader for Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) climate change resilience in Uganda.

The majority of forestland lost is lost to agriculture and urbanisation. The overall impact is not only rising temperatures but also soil fertility, as trees supply crops with water and maintain fertility.

“It is estimated that more than 800,000 ha of crops are lost yearly due to climate change-related events in Uganda. This impacts the country’s food security status,” Dr. Zziwa stated.

Efforts to mitigate the damage of climate change

As the consequences of climate change become starker, more initiatives are emerging across East Africa to combat it. In Narok West Sub-County, Kenya, Plant Village, a small non-governmental organisation, works with pastoralist communities to combat food insecurity.

Plant Village has trained small-scale farmers, particularly women from pastoralist backgrounds, to establish and maintain kitchen gardens. Kitchen gardens aren’t dissimilar to other farming methods “Because they are developed procedurally from sowing seeds in the nursery to transplanting with the help of a PlantVillage Moran or field officer”, Brian Sankei, a field officer at Plant Village, elaborated.

Over the past four months, 80 households across Ngoligori and Maji Moto locations have set up kitchen gardens. These gardens provide families with a steady supply of vegetables, such as kale and spinach, significantly improving household nutrition.

“Initially, these communities relied on livestock products like milk and meat. But during droughts, when their livestock perished, they had nothing to fall back on. Now, with kitchen gardens, they have a consistent source of vegetables, ensuring a more balanced diet,” Sankei said.

The primary setback for these communities is water scarcity due to prolonged droughts, which cause crops to fail. To mitigate this, the organization promotes simple rainwater harvesting systems using gutters and storage tanks through training.

The benefits of these kitchen gardens extend beyond food security. Families now earn additional income by selling surplus produce in local markets. Noomali Nkongoni, a mother of four, sells kale and spinach from her kitchen garden at the Sanda Market, near Ngoligori.

“Before, I used to buy vegetables. Now, I grow my own, feed my children, and even make money,” she shares. The money I get has enabled me to pay for my solar-powered system daily, and my home is greener than ever.” Kisinyinye Sankei, another farmer, highlighted that the project has reduced household expenses. “I no longer buy vegetables from the market. The only challenge is the drought. Spinach, for example, dries up quickly if it lacks water,” she notes.

Aside from water scarcity, Brian Sankei adds that the scattered nature of pastoralist settlements makes it difficult to conduct training sessions and track farmers’ progress. Additionally, rough terrain poses logistical challenges, especially during the rainy season.

Unfulfilled Climate Financing

Climate change is a direct consequence of human activity. Beyond local causes (deforestation, mining, etc), Africa is a victim of global factors, mainly the CO2 global emissions of which Africa is only responsible for just 3.7%, according to the International Energy Agency data from 2022.

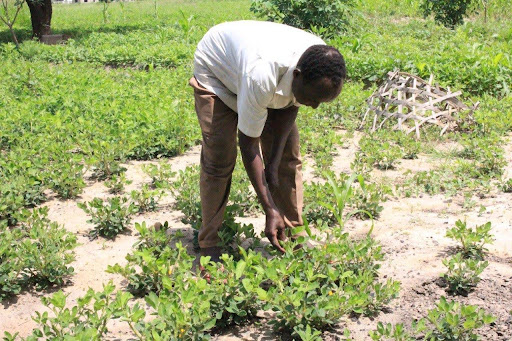

Many hectares of palm oil trees and food crops flooded following the rising waters of Lake Tanganyika video by Rénovat Ndabashinze.

The bulk of carbon emissions causing global warming come from China, the United States of America, and India, the top three emitters, respectively. Unfortunately, African countries are forced to grapple with the droughts and flooding resulting from climate change fueled by the developed nations. It was this reality that necessitated the creation of various climate finance mechanisms, such as the loss and damage fund to developing nations, among others.

A report by Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) revealed that in 2021/2022, Africa received $48 billion in climate finance—a 48% increase from the previous year—yet this remains a fraction of the estimated $250 billion needed annually to finance climate change adaptation and mitigation actions. Most of this funding came from international sources, with domestic contributions making up just 10%.

Multilateral Development Finance Institutions (MDBs) were the largest providers. However, much of this funding was in the form of debt, raising concerns about the long-term financial burden on developing nations. Despite commitments under the Paris Agreement, East African governments still struggle to access adequate climate finance, hindering large-scale adaptation efforts.

The African Economic Outlook projects that Africa will need $2.7 trillion by 2030 for climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. CPI estimates Africa needs $250 billion annually from 2020 to 2030 to tackle climate adaptation. For example, in Uganda, the cost of inaction between the year 2010 and 2050 has been estimated between $273 and $437 billion. Uganda creates an enabling environment to address climate change – the National Climate Change Policy and the Implementation Strategy (2015) and the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), among others.

Uganda, Rwanda, DRC, Tanzania, Kenya, and Burundi all contain stories of despair and resilience linked to drastic changes in climate patterns, which remain an active threat. A study by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) has identified heat stress indicators that could signal impending droughts and floods in the region. While climate-resilience programs and innovations are being introduced in communities, the trauma left behind by past and future floods and droughts will persist.

Additional editorial support by Thomas Mukhwana.This story was produced with the support of the Ukweli Coalition Media Hub.