By Robert Kituyi

April 19 was a win for freedom of expression and information for Kenyans after Justice Mumbi Ngugi declared Section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communications Act – a law that creates the offense of “misuse of a licensed telecommunication device” unconstitutional. In practice, all cases hinged on section 29 before any court are now illegal.

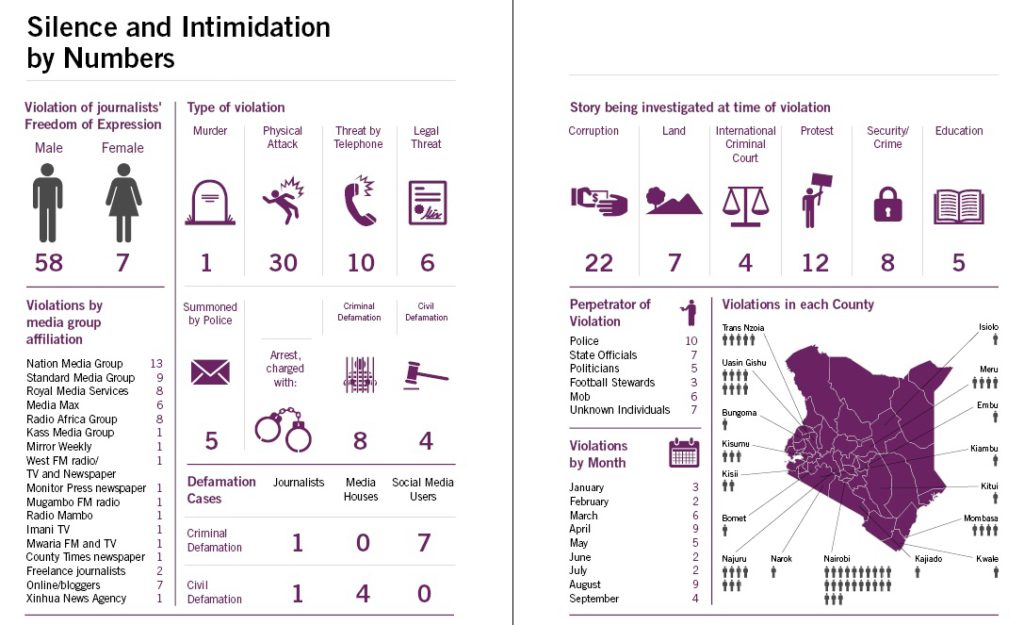

It was increasingly clear that the police and those pulling their strings were exploiting the ambiguities in this provision mainly to intimidate and frustrate their critics with almost impunity. More than 23 bloggers among them journalists have been arrested and charged under this provision since January 2015, according to ARTICLE19 Eastern Africa’s documentation. Seven bloggers and journalists were arrested and charged under this provision in 2015 and 15 from January to March 2016.

This law netted in anyone deemed to have used a licenced communications device such as cell phone or computer to send a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character; including sending a message that one knows to be false for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another person.

ARTICLE19 – an international NGO that defends and promotes freedom of expression and right to information acting in the this petition as an interested party had challenged the provision arguing that the section created an offence without consideration to the mandatory requirements of Article 33 (2) of the Constitution on limitation to freedom of expression. In its submission, they argued that the use of this section amounted to inventing new sets of limitation that are outside the constitutionally sanctioned limitations and hence unjustifiably offended freedom of expression.

Justice Ngugi said this provision which had been in use by authorities to clamp down on bloggers and internet communicators posed “a chilling effect on freedom of expression and information.” The judge declared the section “wide and vague” meaning it lacked clear definition and hence its enforcement disproportionately by authorities.

The provision also fell way off from the scope of the limitations allowed under Article 33 (2) of the Constitution on freedom of expression and information, contrary to the arguments presented by those defending the use of this provision.

While delivering the landmark judgment, Justice Ngugi also noted that the KICA provisions were not intended to apply to individual users of social media or mobile telephony when it was being enacted.

KICA was enacted as an Act of parliament to establish the Communication Commission of Kenya and subsequently in 2013 amended to Communication Authority of Kenya to provide for the transfer of the assets of the former Kenya Posts and Telecommunication Corporation to the Commission.

Among its objectives included the regulation of the telecommunication system in Kenya and to “facilitate the development of the information and communications sector including broadcasting, multimedia telecommunications and postal services and electronic commerce.”

Section 24 of the Act states that the “commission may, upon application in the prescribed manner and subject to such conditions as it may deem necessary, grant licences under this section authorising all persons, whether of a specified class or any particular person to; operate telecommunication systems; or provide telecommunication services, of such description as may be specified in the licence.

“Individuals such as the petitioner and others who post messages on Facebook and other social media do not have licences to ‘operate telecommunication systems’ or to provide telecommunication ‘as may be specified in the license’, justice Ngugi ruled.

Lack of clear definition in the Act of the words ‘grossly offensive’, ‘indecent’ ‘obscene’ or ‘menacing character and by the fact that the Act was silent on who determines which message causes ‘annoyance’, ‘inconvenience’, ‘needless anxiety’ left the door wide open for abuse by authorities.

“The provisions of section 29 are so vague, broad and uncertain that individual do not know the parameters within which their communication falls and the provisions therefore offend against the rule requiring certainty in legislation that creates criminal offences” she said.

The Attorney General and the office of Public Prosecution while challenging the petitioner argued that the principle of interpretation of statutes that was to the effect that a legislative enactment ought to be construed as a whole and that in interpreting a statute, courts ought to adopt such a construction as will preserve the general legislative purpose underlying the provision.

The AG, further challenged that the words used in the section were clear and that their literal meaning clearly brought out the mischief which they were intended to cure, as well as the cure provided and hence there was absolutely no vagueness in the provision, nor was it overbroad as petitioned.

ARTICLE19 was enjoined in the petition as an interested party after Geoffrey Andare was arrested and charged in April 2015 for posting a message in Facebook that reprimanded an agency official for allegedly sexually exploiting young girls in exchange for scholarships.

Andare wanted the provision declared unconstitutional and invalid for unjustifiably violating Article 33 of the Constitution. Through his lawyer Demas Kiprono – a senior program officer at ARTICLE19, he argued that the continuous enforcement of this provision violated not only his rights under the Bill of Rights but also militates against the public interest, the interest of the administration of justice and constitutes an abuse to the legal process.

He also sought termination of his case after the law is declared unconstitutional.

Andare had argued that the section was vague and overbroad and that it had a chilling effect on the guarantee to freedom of expression, and that it created an offence without creating the mens rea [the intention or knowledge of wrongdoing] an element on the part of the accused person.

The AG and DPP maintained that the section was in fact constitutional and a permissible limitation under Article 24 of the Constitution an argument that was dismissed in the ruling.

The judged ruled that provisions on reputation and character maligning are clear in defamation laws. The AG and DPP had argued that the purpose of section 29 of KICA was to protect the reputation of others.

Justice Ngugi also took a swipe at the government authorities for their general presumption that every Act of Parliament was constitutional, and that burden of proving the contrary rested upon any person who alleges otherwise.

In challenging this misnomer she said the constitution under Article 2 makes it clear that the “Constitution is supreme and any law that is inconsistent with the Constitution is void to the extent of the inconsistency”

The Director of Public Prosecutions will now have to reconsider whether or not to proceed with the prosecution of bloggers and journalists accused of misuse of telecommunication gadgets under defamation laws.