By Winnie Kamau/UNFPA

TELA, Honduras – In the early 2000s, even as the AIDS epidemic began to wane, one country in Central America remained disproportionately endangered by the virus: Honduras.

At the time, more than half of all cases in Central America originated there – and several communities in the country, including LGBTQIA+ people, were hit harder by the health emergency than most. Among them were the Garífuna, an Afro-indigenous ethnic minority in Honduras, UNAIDS estimated the HIV prevalence rate to be at more than 8% in 2003, six times the national average.

“They said that we Garífunas were going to disappear [because of AIDS],” said 74-year-old activist Bertha Arzú, reflecting on the epidemic.

The AIDS crisis was far from the first time the Garífuna people had faced an existential threat. Their culture, born from the historical intermixing of Africans who had escaped enslavement with the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, had survived centuries of forced displacement, repeated rights violations and marginalization.

Against these and other health challenges, Ms. Arzú took a stand for her community. In 1996, she founded Enlace de Mujeres Negras de Honduras (ENMUNEH), which for more than 30 years has advocated for the rights of Black and indigenous women across the country.

“Bertha Arzú pioneered the struggle of Black women in terms of empowerment and the defence of women’s rights,” her colleague, Lusy Fernández, told UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency. “[She is] the reference [point for] Black feminism here in Honduras.”

Creating Connections, Changing Lives

Ms. Arzú was born in Tela, Atlantida, on Honduras’ northern coast, in 1949. As a girl, after visiting the hospital with her mother, she decided on a future in healthcare.

“When I was 9 years old, I said, ‘I’m going to be a nurse in a white uniform,’” Ms. Arzú told UNFPA.

virus in Roatan Honduras /Reliefweb

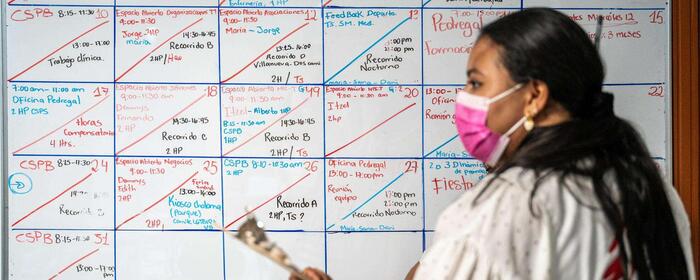

Her choice of career would prove life changing for her and thousands of other women and girls – the future beneficiaries of ENMUNEH. For almost three decades, the group has worked to promote the rights and health of Black and indigenous women in Honduras by collaborating with and training midwives, gathering and analyzing data, and raising awareness of sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Access to health services and information has long been a major issue among the Garífuna. “Before, there were no roads, no doctors, no health centres,” Ms. Arzú said, describing one manifestation of the widespread inequality her people still face.

Across Honduras, Garífuna communities disproportionately experience extreme poverty, systemic racism, forced displacement and exposure to health risks such as HIV. Researchers have linked the disproportionate prevalence of the virus among the Garífuna to the group’s history of labour migration, itself tied to a lack of employment opportunities.

Ms. Arzú was among those who sought to turn the tide on the HIV/AIDS crisis. In 2003, her organization launched a programme to encourage Garífuna people to practise safer sex while centreing human rights. It also employed various strategies to “improve Black women’s self-esteem and encourage their empowerment to break cycles of physical and sexual violence,” according to Ms. Arzú.

“The path to a world free of AIDS begins and ends with human rights – the right to knowledge that is accurate and unbiased; the right to be treated with dignity and respect; the right to feel safe, no matter who you are or who you love,” said UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem.

Improving the World for Women and Girls

Around the globe, the rate of new HIV infections has slowed. And between 2016 and 2022, according to the Global Fund, fewer than 5 per cent of cases in Honduras involved Garífuna people.

Though the virus and other health risks continue to disproportionately affect the Garífuna community, ENMUNEH has had a clear impact on many of its women and girls. “It changed my life for the simple reason that I [came to know] my rights, my duties, and I also knew how to teach other women,” said Maria Miranda. “I thank [Bertha] very much for having been by my side, by the side of all the women.”

“The legacy that I leave to my granddaughters and my daughters is that they do not forget our communities, because now they are being lost,” Ms. Arzú told UNFPA.

Adding “We are all going to leave this world. But let us leave something, a memory.”