PART 1

By Mary Mwendwa and Christian Locka

Kenya and Cameroon: Farmers in Kenya and Cameroon are using chemical pesticides containing molecules that are considered harmful and dangerous to human health and the environment. These pesticide molecules have been banned in the European Union Markets hence raising concerns about why they are still widely used by farmers and supplied by agrochemical giants.

A collaborative investigation by our Journalists has established that Chemical Pesticides that are already banned within European Union (EU) markets are still being used in Kenya and Cameroon. These pesticides containing hazardous molecules have been flagged as dangerous to human health and the environment. Scientific studies have also proved that the said molecules are responsible for certain diseases including some types of cancers. These chemicals of concern are readily available to small and large-scale farmers who are ignorant of their effects.

Kenyan Scenario

Acephate, chlorpyrifos, imidacloprid, carbendazim, and mancozeb are some of the molecules this investigation found being used by farmers. All are registered and approved for use by farmers by the Pest Control Products Board(PCPB) a regulatory and pest control products body in Kenya.

These chemical products are manufactured by companies from Germany, India, China, and the USA.

Acephate Insecticide and Chlorothalonil fungicide molecules were common chemicals that we found farmers primarily using to control aphids (small sap-sucking insects) , in vegetables and in horticulture. Tomatoes were one of the crops that are sprayed with this chemical.

American National Pesticide Information center (NPIC) describes Acephate as an organophosphate insecticide. It is used on food crops, citrus trees, as a seed treatment, on golf courses, and in commercial or institutional facilities. At one time acephate was used commonly in and around homes, but most of those uses are no longer allowed. Acephate has been registered by the U.S. EPA since 1973.

Similarly, the Mancozeb molecule was a fungicide that we never missed with all the farmers that we interviewed. It is used to control potato blight.

At the same time, at least 42 products are registered under Imidacloprid which is used to control pests in plants such as coffee, cabbage, kale, maize, tomatoes, French beans, chilies, sweet potatoes, coriander, melon, spinach, and beans. Bamako, Click, confidor, ovados, and thunders are some of the brands we found in use. They are manufactured locally and distributed by Twiga and Syngenta giant companies.

These molecules have been banned for use in EU markets and were among others listed by non-governmental organizations who tabled a petition to Kenya parliament in 2019 for their withdrawal from Kenyan markets.

The petitioners demanded an immediate withdrawal of the chemical pesticides because of their harmful nature. The Pesticides Control Products Board (PCPB) was tasked to review 30 pesticide products that were of concern, as tabled in a report by a Civil Society Organization Route to Food.

The review is ongoing while farmers continue to use them.

For example in Kenya’s Taita- Taveta County, Taveta Sub-County, Jackson Mwendwa aged 33, a father of one is a small-scale farmer in Riata Kubwa village. He has been farming since 2017. He uses a variety of pesticides and he has no idea of how harmful they are. He has planted in his 2-acre farm kales, cucumbers, bananas, pawpaw, and tomatoes.

“ I use pesticides to kill pests and fungi that are now stubborn in my farms. I cannot live without using them because I will have no yields.”

He says that he buys the pesticides from a local agrovet. He asked if he was aware of any dangers, and he said no one had told him about the harmful effects of the pesticides he used.

“No one has ever talked to me about the dangers, I just want to get rid of the pests that are now very stubborn,” he says.

Taveta is a dusty and hot humid town bordering Tanzania with limited unpredictable rains. It is located approximately 360 km southeast of Kenya’s capital, Nairobi.

Here, farmers do subsistence farming for their livelihood despite the unpredictable rain patterns. They use water from snowcapped Mt.Kilimanjaro springs for irrigation.

At the same time, Joshua Ngusia has been practicing farming since the early 80s and was also employed as a supervisor at a farm. He explains how pests are becoming stubborn due to shifting climatic patterns.

“Pests are becoming more vicious each passing day and therefore as a farmer, I have no choice but to visit agrovets and get a solution. I buy the pesticides here at the shopping center. I know they are harmful but I have no choice because I need to make a living.”

Ngusia reveals that agricultural advisory services have reduced since agricultural services were devolved. “We occasionally get extension services where companies like Twiga visit us and advise us on farming methods, they usually come with pest control products which they recommend for use on specific crops.”

Stanley Katua, a youth aged 22 is a farm worker at Machungwani farm, Kivalua village. He has worked for one year on a farm where he uses pesticides regularly. He sprays bananas, beans, maize, and potatoes.

“I spray these crops at least once per week and harvest when ready.”

When asked about protective gear, Katua said that it is an extra cost that his employer cannot afford to give him. “I just use my normal farm clothes, at times I get irritation on my skin but I have no choice but to soldier on to eke a living,” says Katua.

The central Kenyan County of Kirinyaga is one of the top agricultural regions in Kenya. Farmers here are known to supply their produce to various places including exports. It takes approximately two hours to Kagio town where we meet farmers who are using pesticides in Mukithi village.

Joshua Muremi is an agro-dealer and a tomato and rice farmer. He is one of the few farmers who are aware of the dangerous molecules and is worried if something is not done in the next 10 years, a disaster will strike with venom.

He mentions acephate, mancozeb, and chlorpyrifos molecules. He says snails have become stubborn in his rice field and uses chlorpyrifos molecule products to control them. “I am very much aware that these pesticides are harmful but what else do I use, I need to make a living.”

Muremi notes with a lot of concern that decades ago bananas were not sprayed. “We are spraying bananas with imidacloprid molecule injected into banana flowers to control thrips,” he says with a lot of concern.

Leah Wangui a mother of two and also a vendor at Kagio market similarly uses most of these pesticides to spray on her farm. She has planted kale and pepper which she sells to local buyers.

“I just walk to the nearest agro vet shop to get the pesticides, I mix and spray them by myself to minimize costs.”

She confides that she is aware that crops should be harvested at least 3 to 7 days after spraying but at times she is forced to harvest immediately after.

The recommended time to harvest any crop after spraying is 3-7 days. Some farmers do not follow this and harvest crops while their residues are still active on the surface of the crops.

Health Concerns

These pesticides that have been banned in EU markets have proven to be dangerous to human health and some terminal diseases like cancer are linked to them.

Although gaps in cancer research exist because of many factors, resources being a top barrier, cases continue to rise in Kenya, Cameroon, and many other African Nations.

Ephantus Maree, Head of Department at the Ministry of Health confirms that by 2014-2016 27% of deaths were attributed to Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs), and by now has risen to 40%.

This data includes cancer on the top list.

”We can confirm that the incidence of cancer is on the rise and several risk factors are responsible. Environmental, where chemical pesticides linked, tobacco and alcohol use, lack of exercise, genetic and many other factors.”

Maree further says they cannot exactly point out which risk factor is contributing to high incidences of cancer but stressed that all the mentioned ones were responsible.

He points out how critical data is needed in the fight against cancer.

“In the world of cancers, the numbers have to be there. In Kenya, we have established registries that will help get the numbers. We have data but it is not adequate.”

Adding “Lack of resources is our biggest challenge in having accurate data on cancer incidences in the Country,” says Maree.

At Texas Cancer Centre, a private cancer treatment and care center located in Kenya’s capital of Nairobi. The facility is owned by Dr. Catherine Nyongesa who is an oncologist. She confirms how cancer cases continue to be on the rise, “We have treated over 10,000 cancer patients since 2010 when Texas was founded.”

She says 60% of cancer cases are mostly women “The biggest burden of cancer is breast, cervical, prostate, and esophageal and now colorectal cancer is increasingly becoming common,” says Dr. Nyongesa.

Adding “Colon cancer is quite common and takes number 6 in global statistics after cervical and breast cancers.”

Nyongesa agrees with the fact that there have been controversies around pesticide usage in Kenya and their relation to increasing cancer cases.

“In medicine something has to be backed with research, having said this the rising trend in colorectal cancers has been linked to a high-fat diet and sometimes pesticide use where people eat maybe vegetables that have pesticide residues and have not been well washed.”

Nyongesa adds that cancer risk factors are many, some are known and others are not known.

At the reception which also serves as a waiting area, patients stream slowly seeking treatment and palliative care for different types of cancers.

A few minutes at this waiting bay clearly paints a rough picture of how the cancer burden is rising each passing day in Kenya.

The pain, weak patients, some with their jaw bones protruding, others with catheters walk in slowly hoping to beat the monster that now stares at Kenya’s health sector in the face.

John Allan Mbanda aged 67 a father of five is receiving treatment at the Texas Centre. He beams with joy as he narrates to us about his journey as a colon cancer patient.

A drip of water is inserted through his finger before medicine for his chemotherapy is put in.

The room is full of patients, both on medicine and water drips. Some were asleep, some writhing in pain, and others occasionally smiling at us, ready to share their stories.

A cloud of pain and a light of hope fills this room.

Mbanda recalls how early this year he started having a blotted stomach and used to vomit a lot “My family got worried about the vomiting and blotting of the stomach and decided to take me for a check-up at a hospital. Samples were taken and a tumor was found growing in my intestines and surgery was recommended. I was immediately put on chemotherapy where I did 12 cycles.”

Mbanda confirms that the treatment he received helped him and eased his pain. However a month ago when he came to Texas for a check-up he was told to get another 6 rounds of chemotherapy cycles of treatment because they found out the tumor was growing again.

“If you see me you cannot tell that I am a colon cancer patient, I’m hopeful that one day I will be completely free from colon cancer,” he says.

Angeline Kitavi aged 50 is also a cervical cancer patient. She has traveled from Machakos County in lower eastern Kenya for treatment. She used to be a farmer who farmed vegetables such as kale and spinach. She confides that she has used pesticides for a very long time. “I have been using pesticides to control pests on my vegetables for over 10 years.”

In 2019 she started bleeding abnormally and had a foul smell from her urine.

“I used to bleed a lot and after urinating a very bad smell could come from my urine. I was also in much pain without knowledge of what I was suffering from. Later I was diagnosed with cervical cancer. I come here for my treatment and I hope to recover” she explains.

Several other patients were mainly suffering from cervical and breast cancers, which are mainly treated here at the Texas Cancer Center.

Dr. Nyongesa points out how Kenya is still behind in research on cancer “There is always limited funding for research. Now the University of Nairobi makes it mandatory at masters for oncologists to do research on cancer, I know this is not enough but as a Country, we are headed in the right direction” she says.

The National Cancer Institute of Kenya reports how the cancer burden is rising globally. They say in Kenya, cancer is the 3rd leading cause of death after infectious and cardiovascular diseases. They also note research done by The International Agency for Research in Cancer (IARC) GLOBOCAN report for 2018 estimated 47,887 new cases of cancer annually with a mortality of 32,987.

This represents around a 45% increase in cancer cases compared to a previous report of 2012 which estimated 37,000 cancer new cases with a mortality of 28,500 respectively.

Breast, cervix uteri, esophagus, prostate, and colorectal are the new types of new cancer cases in both females and males. Oesophageal, cervical, and breast cancers now lead to cancer deaths.

Similarly, breast, kidney, ovarian, pancreatic, and stomach cancers are some of the cancers linked to pesticide exposure.

In June 2021, an authoritative report by the French research institute INSERM, based on the review of more than 5,300 scientific studies confirmed a link between pesticide occupational exposure and six pathologies, including three cancers: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), multiple myeloma and prostate cancer.

The other 3 diseases associated with pesticides are Parkinson’s disease, cognitive disorders, and certain respiratory system disorders such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis.

Toxicological Studies

Dr. Laurence Huc, Director of Research INRAE, member of the project PREHEAT (Interdisciplinary approaches to pesticide-related health effects in Africa/Tanzania) conducted a toxicological study of pesticides used in Tanzania together with Liana Arnaud in 2022. They found out that most of the pesticides they sampled had health hazards.

Some of the health hazards they established were neurotoxic, carcinogenic, genotoxic, immunotoxic, reprotoxic, endocrine disruptors, kidney disorders, and digestive and pulmonary diseases.

They studied several pesticide molecules which included Mancozeb, profenofos, Chlorpyrifos, Cypermethrin, and Deltamethrin among many others.

Mancozeb was a common fungicide that was highly used with at least 103 formulations.

Dr. Huc noted that Mancozeb was found to have an endocrine disruptor effect in humans, which means that it interferes with the hormonal system of the body.

Other dangers included reprotoxic and developmental hazards.

Mancozeb was banned within the EU in 2021 but ironically is authorized for use in Tanzania.

Dr. Huc further noted that there is no safe use of pesticides, neither for professionals, people in the vicinity of crops, or consumers.

“Use of pesticides exposes the population to serious and severe diseases: cancers, neurological diseases, chronic kidney diseases, infertility, malformations in children, among others.” Adding that “Environmental contamination also affects all ecosystems, even at a distance from treated crops”.

She recommended that, while governments promote environmental health and the sustainability of food production, it is appropriate to consider limiting the use of pesticides and implementing agro-ecological methods to support farmers in changing their practices.

Cameroon Case

In Cameroon’s economic capital Douala, the Sandaga market is well known as a place where fresh food is sold. Few people know, however, that in the middle of the anarchically arranged stalls are stores selling pesticides. Every day, Jacques, a 46-year-old salesman, invites passers-by to take a look at his stall of about 9 square meters. Some products are placed on a bare floor, others are arranged on wooden shelves; the smaller ones occupy a large part of a wooden table.

“I sell several types of pesticides, but the problem is that some farmers don’t know the names of the products; in this case, we ask them what they want to do and we suggest a product,” says Jacques, who has a first degree, before adding with a smile: “It’s true that we’re not experts, but we still give advice on how to use them”.

Jacques is right to point out that he is not an expert. If he were, he would have known that one of the products he offers to his customers is a pesticide forbidden to be sold in Cameroon. Captafol, a fungicide used against diseases that attack fruits and vegetables, should not be on Jacques’ shelves. “If a product is banned, it is the authorities who must prevent it from being on the market,” said Jacques. “We, at our level, just want to sell and satisfy the customers,” he says.

Like Jacques, many pesticide sellers are more concerned with making sales than ensuring that their products are legal and of good quality. For several years, the government has made available lists of pesticides registered in Cameroon to the public. The latest list, which dates back to 2021, also includes active ingredients and products that are banned for their acute and long-term toxicity and environmental effects.

These include products such as Captafol, Dinosebe Acetate, Dinosebe, Binapacryl, Cyhexatin, Dieldrin, Aldrin, Heptachlor or Carta. These products coming from Europe are described as “extremely” dangerous when they come into contact with the mouth or skin.

However, these warnings about the danger that pesticides can represent do not discourage farmers like Derik Kadji. The 30-year-old father of two owns a plantation of more than 20 hectares of plantain in the town of Loum, about 100 km from Douala.

“We can no longer do without pesticides,” said the farmer. “It’s what keeps our plants standing because we don’t even know when it’s going to rain anymore with the changing climate,” says Derik, who was born into a farming family.

Derik notes that when his parents worked the land, he didn’t see them using industrial pesticides “But, the soil we use today is very contaminated with insects, so we have to turn to pesticides”.

Derik said that it is not enough to use pesticides to be satisfied with his plantation. He said that any user of these products should be aware of their danger to health and the environment.

“The pesticide does not disappear quickly to the ground, even after a year you can find it,” Derik says, adding “You can, for example, pass in the morning, you put the “Mocap” at the bottom of the plantain, the child who is ignorant passes with his bread by there and as soon as this bread falls there, he will pick it and eat it without knowing what was on the ground because the “Mocap” has the same color as the soil. So if the child eats this soiled bread, he can die,” he says.

Roger Toka is the Director of the pesticide sales company called La voix du paysan agricole (LVDPA). He is supplied by a businessman who imports pesticides from the European Union. “We sensitize the farmers who buy our products by organizing training sessions on the respect of precautionary measures, the techniques of use, and the new products available,” said Toka.

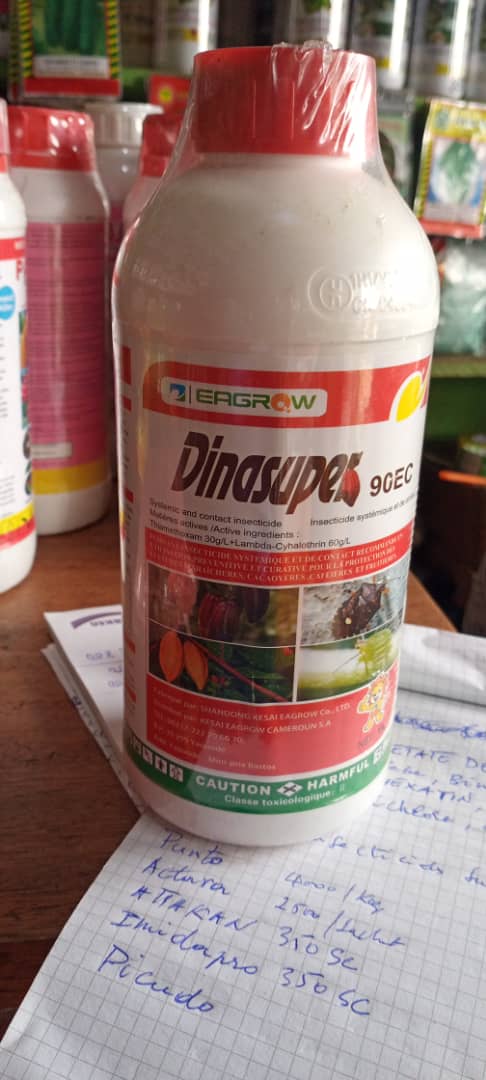

In an investigation titled “Banned Pesticide Exports: Loopholes in Swiss Regulations,” the Swiss NGO Public Eye confirmed that pesticides banned in the European Union (EU) because they are dangerous to health and the environment have been exported and registered in Cameroon. This investigation found that Chlorothalonil, a carcinogenic substance banned in the European Union due to groundwater pollution, is listed as a pesticide registered in Cameroon. The same is true of propiconazole, a fungicide classified as toxic to reproduction, or Thiamethoxam, an insecticide implicated in the collapse of pollinating insects.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu

[…] article was developed with the support of Journalismfund.eu . You can read PART 1 of this pesticide investigation […]

Comments are closed.