By Pierra Nyaruai

Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya’s former Deputy President, Rigathi Gachagua has accused the Kenyan government of inciting the resurgence of the Mungiki sect. The news revived alarm over the alleged revival of Mungiki for political control, but parallel traditional groups have been emerging, enforcing backward practices under the guise of cultural preservation.

These groups, including Gwata Ndai and Mihiriga Kenda, share historical roots with Mungiki and are gaining prominence among young, digitally-savvy Kenyans in their 20s and 30s. Their rise, marked by strict enforcement of traditional practices and rejection of Western influences, comes at a time when Gachagua warns of politically sanctioned intimidation in the region, highlighting a complex web of cultural manipulation, political control, and systematic oppression of women.

In his book, Facing Mount Kenya Kenya’s First President Jomo Kenyatta writes “No proper Gikuyu man would dream of marrying a girl who has not been circumcised…” However, female genital mutilation is illegal in Kenya. It had been since 2011, when Kenya passed the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act, making it a criminal offense to practice FGM, procure FGM services, or take someone abroad for FGM. The law imposes imprisonment for a term of not less than three years, or to a fine of not less than two hundred thousand shillings, or both.

Traditionally, once they come of age, Gikuyu girls would undergo a ceremony called mambura to celebrate their initiation, Irua, with the act itself called kuhetwo. Kenyatta writes that initiation is a deciding factor on whether a girl becomes a woman. The initiation is done before the girl begins menstruation, (they check), so that her first blood is poured to connect her to the ancestors.

The anti-FGM campaign was begun and championed by the missionaries, who termed the practice as barbaric. The missionaries banned anyone who wanted to continue with the practice from attending the church or missionary schools. The practice seemed to have died down, but the traditional groups have brought it back with vehemence. And the followers are dedicated to keeping it alive.

The cultural phenomenon is not new. In fact, it is more of an ember that flares up often. The current groups borrow a leaf, or the tree entirely from the Mungiki, an outlawed group. An ex-Mungiki member terms Mungiki a ‘living stone’. These new groups are sort of neo-traditional, thanks to their sheng-speaking, Tiktok-using members. The members of these groups lie on the bed of Kikuyu tribal ethnicity and shun Westernization in all its forms. They sport disdain for anything that is termed modern, especially religions like Christianity. The members of these groups are predominantly in their 20’s and 30’s.

There seems to be an overall theme in their belief, which is “gucokia rui mukaro’ which translates to ‘returning the river to its source’. The concept is generally, to bring back the Gikuyu nation to its way of life. One of the ways that the practices rooted deeply in Gikuyu culture is female genital mutilation, specifically, clitoridectomy.

Uncircumcised women are branded ‘kirigu’ in a scarlet manner kind of way. Men are not allowed to court her and women are not allowed to fraternize with her. Apart from the practice being a step into womanhood, it is also an indication of purity and innocence. Uncircumcised women on the other hand are rumored to be promiscuous, with a perpetual sexual angst. Older generations of Gikuyu women hold the belief that HIV/AIDS was a curse brought down to punish the women who had not been circumcised. The gospel is spread on social media, using ethnic language that the algorithm finds hard to flag as harmful.

The fact that FGM is illegal in Kenya did not deter Susan’s * husband from trying to get her circumcised. He had been on a quest to ‘find himself’ and ended up joining a cultural sect, one of many that have gained popularity in Kikuyu culture. The groups go by different names, with the most popular being “Gwata Ndai” (Riddle Me) and “Mihiriga Kenda” (The Nine Clans).

Susan * had been married for three years when her husband joined the Gwata Ndai group. The changes in his lifestyle began subtly but grew in prominence as his involvement deepened. “It started with not going to church and denouncing Christianity entirely. He did not want to see the bible, a cross, or hear Christian music in the house. He stopped drinking tea made with tea leaves and wanted me to stop working to become a stay-at-home wife. He began insisting on having anal sex because I was too ‘unclean’ to have it any other way. The last straw was the day he brought three men into our home and demanded that I be circumcised. He was very adamant and I figured that I was in danger. So I pretended that I was going along with it and reached out to an organization that helped me plan my escape. I am now safe in my parent’s house.”

The investigation reveals that there are women who are seeking these services willingly, in a bid to make amends with their ancestors or as part of their spiritual journey.

Agnes* a 26-year-old got circumcised three years ago in Kiambu. “I think I was going through a phase then. I was struggling with my faith and was looking for a new way to channel my beliefs. I had just transitioned from Christianity when I looked into astrology and then one night on TikTok, I came across a live where people were discussing traditional Kikuyu beliefs. I felt strongly that this was what I needed then, so I went down a rabbit hole. Things happened so quickly and before I knew it, I was in a house in ushago with a blade. The lady who did it could have been my grandmother. She seemed very proud of the step I was taking. The procedure itself was so quick and I sat on salt water for about a week, then it was done. Nothing in my life changed as a result. There was no magical good fortune or anything, nothing in my life changed as I was made to believe. “

In 2023, the news was awash with the story of Simon Kimani, who drowned his mother in a well before jumping in the same well because she disagreed with his new beliefs that championed for female genital mutilation. The stories are hushed down, but some women seek the help of local authorities for salvation. Senior Chief Wangai in Githunguri received a report and he took charge and prosecuted a man who threatened both his wife and mother in law with circumcision. However, he died before the prosecution began.

Joining these groups is cemented by oath-taking, which creates a sense of machismo. The process of cutting a woman’s clitoris is not just a physical one, it is a psychological one. The process is supposed to make women docile and submissive by taming their sexuality. The need to subdue women is a nuance that has been embraced largely by male populations online. The manosphere thrives on messages of domination, male superiority, and female submission.

Throughout history and into the present, patriarchal systems have evolved methods to control women’s autonomy and sexuality. In traditional societies, such as the ones emerging, these controls often manifest through cultural and religious practices that restrict women’s choices, enforce rigid gender roles, and maintain economic dependence. Cultural ceremonies such as “kuhetwo” become tools to reinforce these power structures, while community pressure and social stigma serve to maintain compliance.

Modern patriarchal control has adapted to contemporary settings while maintaining similar core objectives. Digital platforms have become new venues for radicalization and pressure. Social media spaces are used to amplify the message of these traditional movements. As discussions on such topics deepen, it creates a modern version of traditional behavior control.

The striking parallels between traditional and modern systems reveal their shared foundation. Both focus intensely on controlling women’s sexuality and reproductive choices, wielding shame as a powerful weapon. These systems consistently resist women’s education and independence, often justifying their actions through appeals to nature or tradition. For instance, if the man decides that he is to follow this new way of life, he expects his wife to follow suit without question.

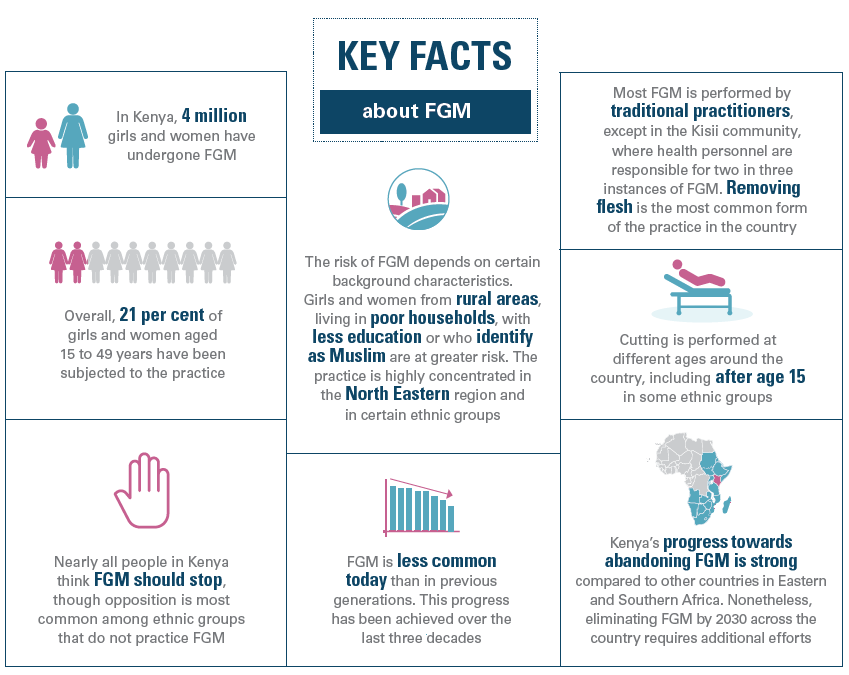

The concept of oath-taking restricts women from raising their voice when they undergo circumcision, due to the fear of curses or death. Dr. Nahya Mukami, who runs the PeonyWave Initiative and offers reconstructive surgery for FGM victims nods that women from the Gikuyu community are actively practicing FGM. “Young girls resort to FGM because they believe the lack of it causes them to fail in life. They want to make things right traditionally.” As a medic actively working in female genital mutilation, she currently has 219 women and girls on her waiting list for reconstructive surgery. The reconstructive surgery costs an average of 1 million shillings (about $6500), a price tag that it out of reach for many patients.

According to The World Health Organization, FGM has severe physical and psychological consequences that can impact a woman throughout her life. Immediate complications of the act can include severe pain, bleeding, infections, and trauma. Some women experience shock or die from these initial complications.

The long-term physical effects often include chronic pain, recurrent infections, complications during childbirth, and difficulty urinating. The procedure can lead to the formation of scar tissue, keloids, and cysts, while also causing ongoing menstrual problems. During childbirth, women who have undergone FGM face higher risks of prolonged labor and obstetric fistulas.

Psychologically speaking, survivors frequently experience anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Many report feelings of betrayal, especially when the procedure was performed by family members or trusted community members. Sexual dysfunction is a common issue, affecting intimate relationships throughout life. In addition, the impact extends beyond individual women to affect families and communities through increased medical costs, complications during pregnancy and childbirth, and lost productivity due to ongoing health issues.

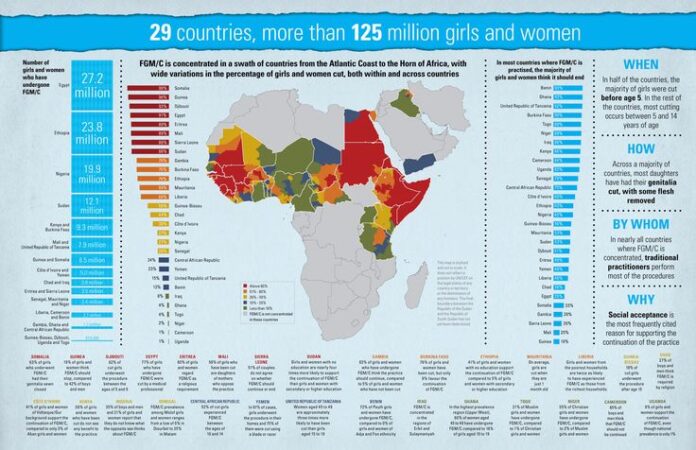

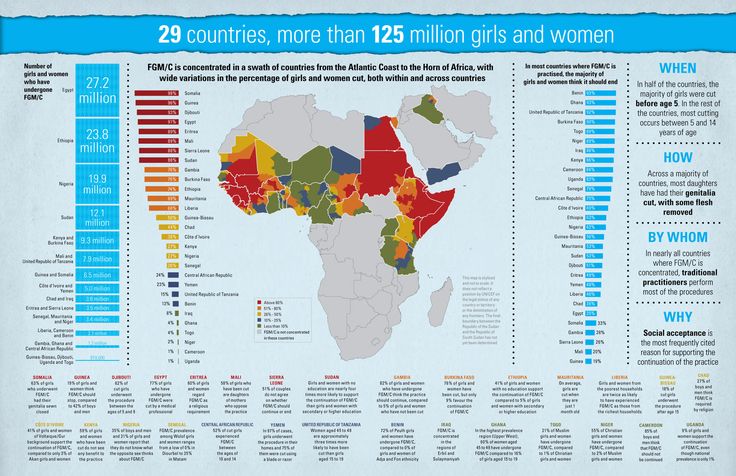

The Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2022 depicts that since 2014, the percentage of circumcised women who were cut and had flesh removed declined from 87% to 70%, while the percentage of circumcised women sewn closed increased from 9% to 12%. It shows that FGM in Kenya is still very much a problem.

Ruth Bange, programs manager at Usikimye, a human rights organization in Kayole states that the organization has done rescues on women who were being forced to undergo FGM by their husbands. “We receive calls from all over the world from women facing gender-based violence, including FGM. In one case, the woman was severely beaten for refusing to undergo the cut in Murang’a. Unfortunately for most of these cases, authorities and other organizations are only informed when the situation has gone south. The silencing makes it hard to get to the women and girls beforehand.”

The anti-FGM campaigns in Kenya are mainly focused on pastoralist communities and the Kisii/Kuria community, while central Kenya remains a thriving hub for trade.

The resurgence and practice of female genital mutilation among young Gikuyu women reveals an intersection of identity, patriarchal control, and generational trauma. It is evident that it is not just a traditional practice, but a calculated mechanism of female subjugation disguised as cultural preservation.

These neo-traditional movements exploit digital platforms, using TikTok and social media to radicalize young people seeking cultural authenticity. They weaponize shame, branding uncircumcised women as impure and sexually uncontrolled, while positioning FGM as a pathway to social acceptance, spiritual connection, and a way to succeed in life.

The psychological warfare is profound. Women are systemically silenced through oath-taking, fear of curses, and community ostracization. It is fascinating to see that the manosphere’s online narratives of female submission seamlessly align with these traditional control mechanisms, creating a dangerous echo chamber that normalizes violence against women.

Despite legal prohibitions and active anti-FGM campaigns, central Kenya is emerging as a stronghold for these outdated practices.