By Sharon Kiburi

Nairobi, Kenya: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket?” an ideology adopted by many wise investors. But, if you logically thought into it, how could putting all your resources in one basket possibly be beneficial?

I venture to explore this in the context of a centralized database system. A centralized database is a place where information is located, stored, and maintained in a single location. This location is most often a central computer or database system.

For a digital identity number, it’s a means of identifying or authenticating the identity of an individual both online and offline, with the information stored in a digital format. Usually, this digital identity is a singular government-issued digital identity (ID).

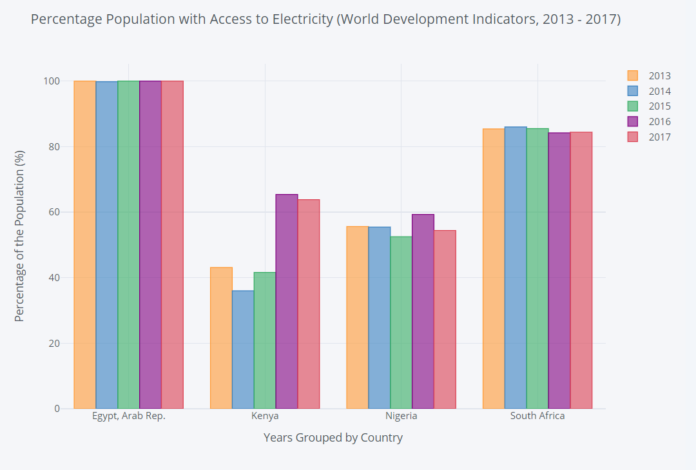

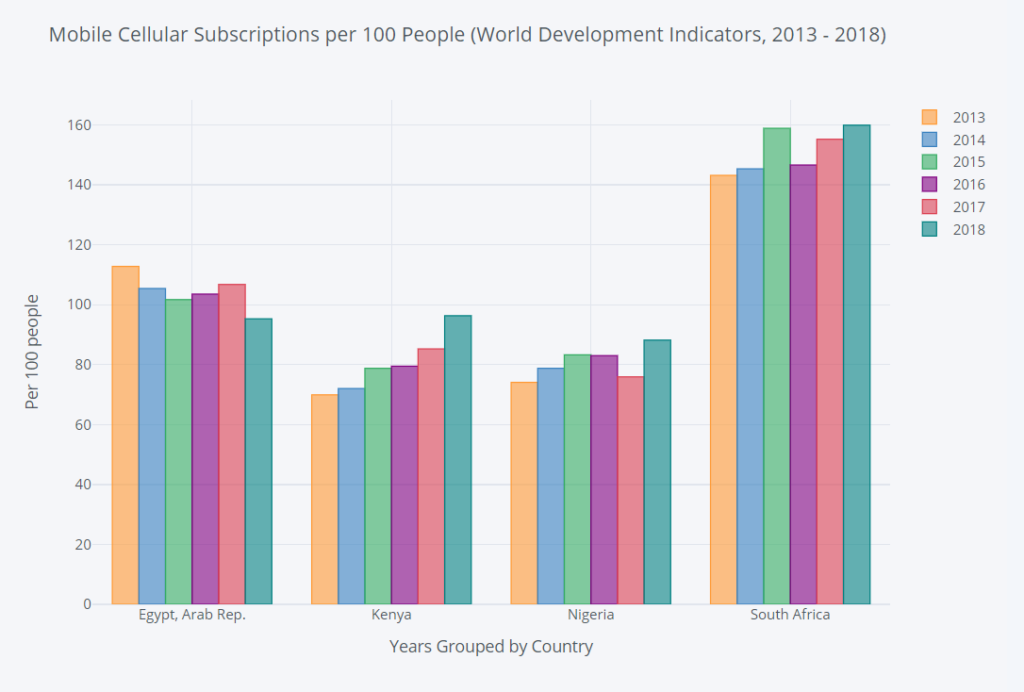

African countries are in a rush to embrace digital IDs, yet mobile subscription rates are still low in some countries. As indicated in the chart below.

I explored Digital Identity in Africa, with a particular focus on Kenya. In twenty nineteen (2019) Kenya introduced the National Integrated Identity Management System (NIIMS / Huduma Number). The Huduma Number would be a digital national Identity that will integrate all one’s documents stored in one database namely the NIIMs.

After the collection of citizens’ personal details which included biometrics, geolocation, profession/career, face photos and iris the exercise raised a number of concerns from inclusion, to human rights and constitutional jurisdiction.

Speaking to experts and professionals in the digital and technology space;

My meeting with Ernest John Ndung’u, a cloud architect in Kenya, was optimistic. He insists, a common location to access everyone’s records will make a lot of things easier for Kenya. First, he says, this would make access to services faster and even more importantly reduce or eliminate duplication. “Gone will be the days when you’re applying for a government-based document and you have to submit all your documents again every time”, Ernest says enthusiastically.

Sectors that would be perfect beneficiaries of this would be the finance industry (Banking, Insurance, Credit institutions) where KYC (Know Your Customer) is the backbone of the service. We also wouldn’t have to carry many cards all saying who we are.

Ernest also states though that information stored in a digital format would be vulnerable to hacking. Privacy is the biggest challenge that befalls this idea. In this modern age, security by obscurity won’t be sufficient. Imagine someone having unauthorized access to your digital identity, accessing all your records; they would impersonate you easily.

The policy might also become an issue, moreover, where the Kenyan people don’t trust the government to use the information as they indicate, especially for political interests.

Referencing the case of Cambridge Analytica , such a data store could be used very quickly for a highly targeted political campaign; all the data one could ever dream of is available in one or two clicks.

Ernest explains the importance for the government to put safety measures in place in preparation for a secure centralized database. First and foremost would be training and vetting of data officers who will be the custodians of the data. Data should be maintained on a strictly need-to-know basis. Regular auditing of the data logs is essential to analyze which firms or institutions accessed the data and reason why.

Andrew Kurgat, a freelance data scientist from the Africa Data School holds a less optimistic view because for a centralized database to work, a lot of security infrastructure has to be set in motion to ensure the data is never compromised, and much work needs to go into building trust with citizens.

Kurgat elaborates, “This approach ensures the government is accountable and responsible for data protection. This is both complex and expensive due to the required multiple layers of security, infrastructure, and highly specialized professionals required to oversee the mechanism.” Therefore, this high-level approach lacks sustainability. However, using cloud services such as Google, AWS, Microsoft, and Oracle is a much more feasible approach because the responsibility is shared between service providers and government employed professionals.

Kurgat continues, “The catch is the need for very strict policies and laws overseeing the operations of these service providers about such data and their will to operate under the necessary and heavy restrictions.” African countries could reference the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union in this regard.

An individual should have a multiplicity of choices on how to present key attributes that compose their identity rather than being forced into a single and rigid system. However, choices over what ID to use are often rendered illusory either in fact or by law. This is especially true for centralized national ID systems since governments often have the power to require national IDs for a range of essential public (and sometimes private) services, according to a report by Mozilla white paper Bringing Openness To Identity.

According to Alice Munyua, policy adviser at Mozilla Africa, “The National Integrated Identity Management System (NIMS/ Huduma Number) is not inclusive to all Kenyans.” This is evident in that, some communities like the Nubians and Namati went to court to contest it; the current national identity card excludes these communities completely and the NIIMS does little to include them.

Alice says the ‘Huduma Number’ requires one to have a legal National Identity card, so one can trace their nationality to their grandparent’s roots in Kenya. However, this is a challenge because most people in the excluded communities do not have either of those things. The problems that prevent some of these communities from getting national identity cards are transferred to the requirement of the digital identity number.

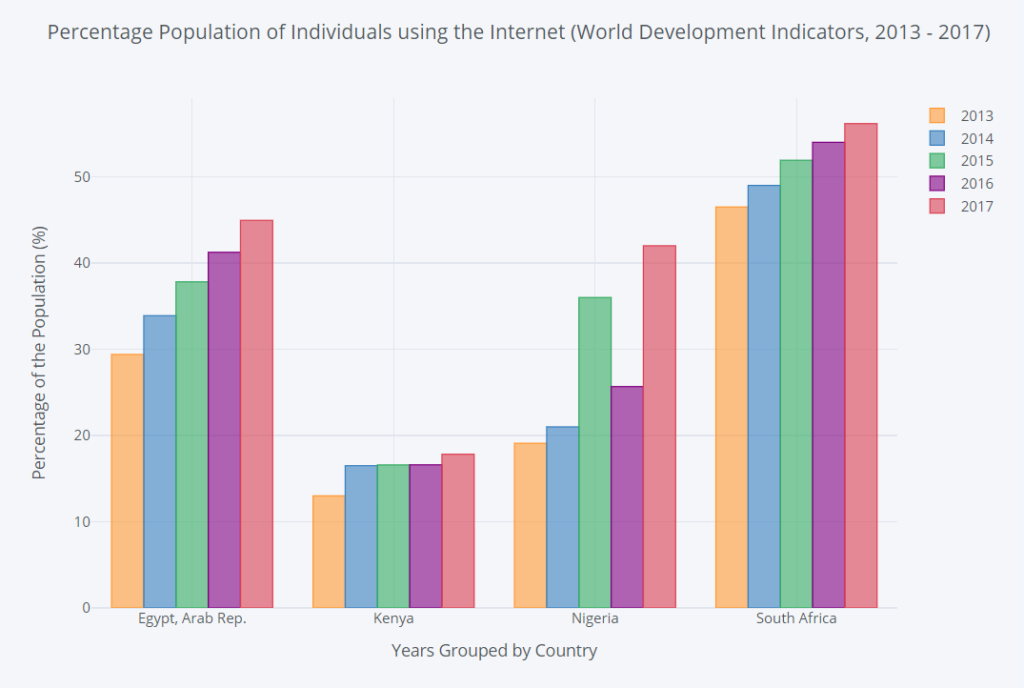

The disparity in access to internet and technology is still huge in African countries and should be considered before endorsing digital identity systems to their citizens. As shown in the data graph below.

If we Africans are to embrace a digital centralized database, what would be the required comprehension level of the citizens in these countries? Says Alice, “Some of the challenges include, in remote areas where people lack birth certificates and cannot prove their ancestors were Kenyan citizens, which are among the requirements to acquire a national identity card. This added to the issues of lack of formal education in these areas poses difficulties.” She explains that there needs to be a thorough consideration of the five elements of good practice for implementing digital identity in the multiplicity of choices, decentralization, accountability, inclusion, and participation.

The identity card in Kenya is such an integral part of everyday life. This ranges from access to services such as health, getting a sim, access to loans, getting a driver’s license, registration for schools, all of which further marginalized individuals.

Hence before implementing digital identity, the issues above need to be tackled. “The illusion that digital identity is more efficient to solve this crisis of marginalized communities is impossible if the same requirement to get national identity still stands in the way of accessing a digital identity number”, says Alice Munyua, the Policy adviser at Mozilla Africa.

The government has not effectively elaborated as yet on how they will protect the information of citizens. This should have been done via meaningful public participation using informative training and feedback collection exercises.

Especially because information such as biometrics and eye iris is sensitive data. Public participation was not widely conducted and neither was the public informed concerning digital identity. The ability for people to opt-out should be provided for without one having to lose access to vital services.

Alice Munyua says Kenya rolled out and implemented NIIMS without any legal framework, although a law was passed in December 2019. There still is no formation of a data protection authority to issue guidelines and regulations. The passed law solves a majority of the earlier issues with the implementation of the NIIMS system if well adopted. If the law adheres to the letter the previous NIIMS system is null and void.

Alice Munyua, Policy Adviser at Mozilla Africa states that there are over thirty-two African countries out of the fifty-two (52) with data and privacy protection laws but there are very few with a data protection authority.

Twenty-three countries are being funded by the World Bank to implement digital identity. The motives for funding African countries to implement technical issues they have not integrated are questionable.

According to Alice Kenya is not ready for digital identity especially with the fact that it did not conduct public participation which is required by the constitution. With public participation, a range of questions should be answered.

For instance, the public should comprehend what digital identity is, they should be able to opt not to have one, the government should provide multiple choices, and citizens should be able to question the necessity of this service as well as the priority and urgency for the country.

A centralized database brings out the issues of accountability, who has access to the data? and the dignity of the individual’s identity.

A centralized database often contains deeply sensitive information (biometrics or even DNA), allows for linking IDs and for sharing ID numbers across many databases, enables enhanced surveillance through the centralized collection of data, and relies on electricity and connectivity for real-time authentication which is often unreliable, exacerbating exclusion.

Alice explains further, “The Kenyan law on data protection is very commendable – it is robust, it took into consideration all the international benchmarks. The law is great! However, if this law is implemented to the letter the exercise carried out early for NIIMS in Kenya is unlawful and the process needs to begin afresh”.

Adding “This is because the law that introduced Huduma number proposes collecting sensitive data that includes biometrics, geolocation, and eye iris, however, the new law states there is a need for structural safeguards before collection of such highly sensitive data,” says Alice.

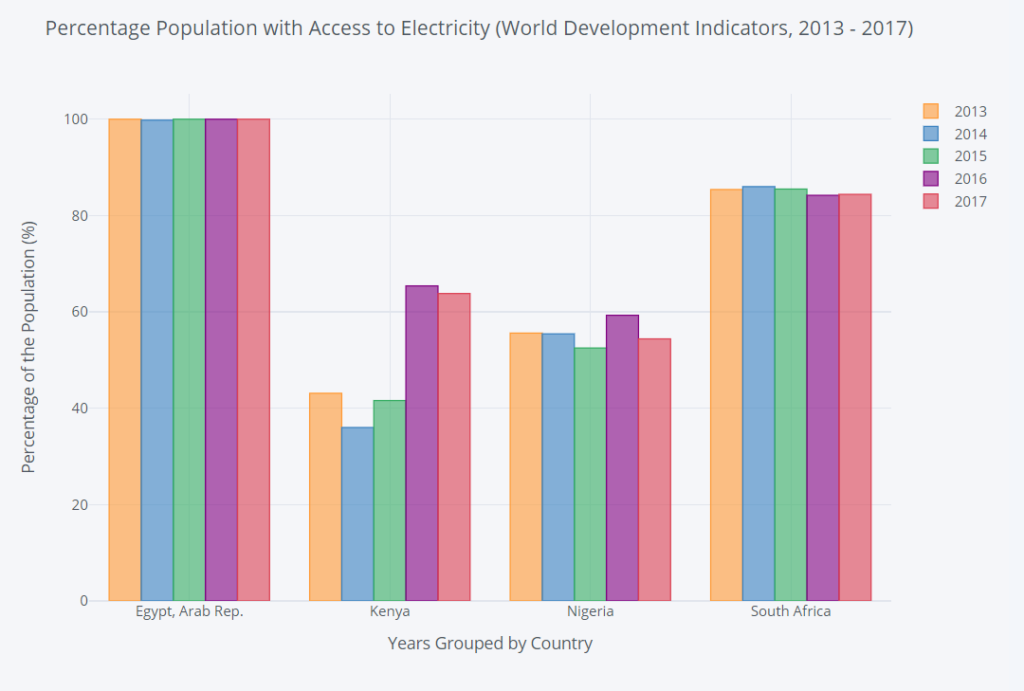

Electricity grid connectivity is also a challenge experienced in African countries, in the wake to go digital and embrace digital Identity systems. Should electricity connectivity be a concern for the government to ensure operations are successful?

Engaging the Nubian rights community, I spoke to Maseke Miriam Rioba in corporate communication. Rioba says the Nubian community faces marginalization in multiple areas including access to adequate social amenities, government processes, and representation in the government.

Rioba further elaborates that the Nubian community resides on a small portion of land in the Kibra slums in Kenya that extends to 288 hectares only. Their environment is characterized by inadequate resources, government restrictions due to a lack of adequate representation, and social exclusion.

The community is constantly challenged with the issue of stereotypes and prejudices, and this affects their access to social services. The community also experiences a lot of discrimination in access to some government services, which in turn infringes on their human rights.

The community faces a challenge in the process of registration of persons because the steps for acquiring IDs have been made extremely difficult for the community.

They have to adduce a lot of mandatory documents for registration and have to go through three vetting stages. The community is also only allowed service two times a week for two hours, says Maseke Miriam Rioba.

Rioba feels that currently the measures being used to implement digital identity are discriminatory since they still include the old systems required to get a National Identity card.

Therefore would not be inclusive of Nubian communities and other marginalized communities. Discrimination comes about where the government requires some vital documents to be presented during the registration process such as birth certificates, death certificates, and national identity cards, yet these documents are not easily available to the Nubian community.

The government did not take into consideration the challenges the people from these communities face to access IDs such as vetting processes and the difficulties in acquiring documents such as death certificates of grandparents. Without ensuring everyone has proper documentation necessary for the registration, the identity would only lead to statelessness for the excluded communities.

“A digital identity would be inclusive for the communities only if there were measures in place to ensure that the documents required for the registration process are available for the marginalized communities”, says Miriam Rioba.

She continues, “For digital identity to be inclusive, the government should ensure communities have an easy time accessing necessary documents, they should carry out education and awareness programs extensively.

Moreover, they need to think of a needs-based approach for any follow-up processes they have on digital identity and consider all communities because if something is meant to be national then all factors that affect communities should be considered and resolved before the government makes policy.

Yassah Musa project manager, also active in the Nubian rights community, says the causes of marginalization in these communities arise from a stereotype that is one of the greatest challenges faced by the Nubian community.

Due to unique factors such as linkages to neighboring countries and their religious status, they are to be stereotyped as refugees, or in severe instances, they get linked to radicalisms that put them at a critical spot with the government agencies carrying out registrations.

He also states that marginalization increases with the lack of adequate representation of these groups in state organizations. Without a present voice in the government, it becomes hard for the communities to enjoy access to rights and social amenities in the community. The other challenge the community faces is that they live in slums. Slums rarely get the attention they deserve and often get below average services.

In his opinion, Yussah says digital identity is a good system. It is less tedious and less costly. However, the issue at hand is not whether it’s a good ID or not. The bigger question is whether we as a developing country are ready to handle mass data and ensure no rights to privacy will be violated. Unless the government has adequate measures in place to include everyone and protect our data, then digital ID is not a good system.

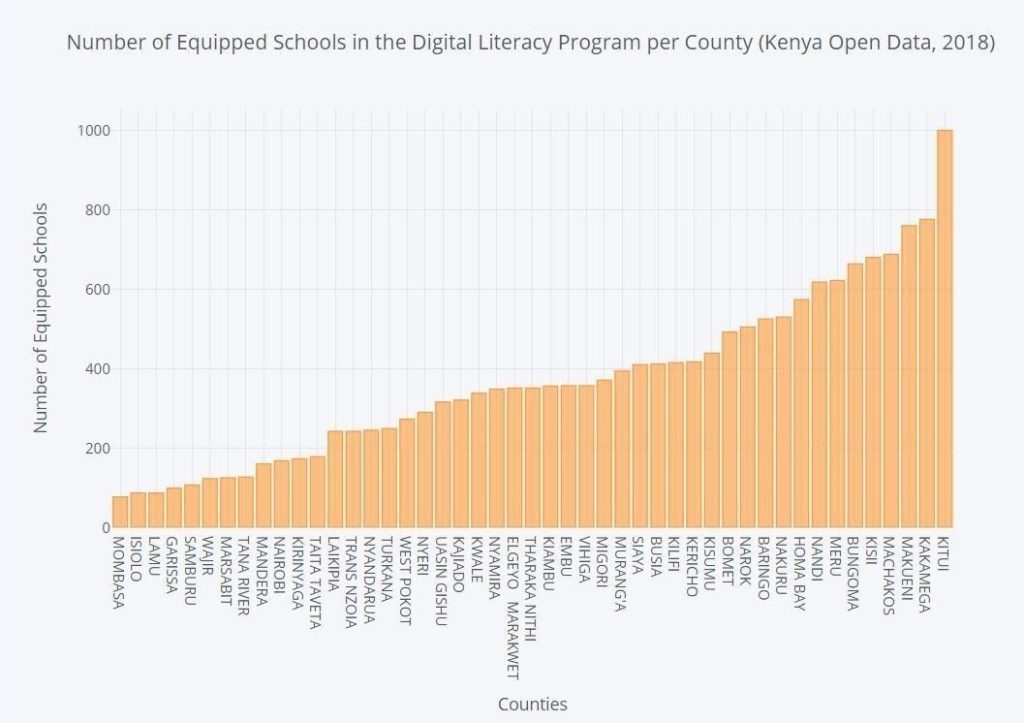

In Kenya digital inclusion is still a work in progress. Below is a chart on the number of schools in different counties integrating digital learning systems; although it is a step in the right direction to ensuring STEM subjects are available to all. The journey still has long miles to be achieved.

It is safe to conclude that African countries are not as yet prepared for a centralized database, this is evident in the lack of infrastructure and systems to support it.

Email: Kiburisharon@gmail.com

Twitter: @Kiburi Sharon

This work was produced as a result of a grant provided by the Africa-China Reporting project, managed by the Journalism Department University of Witwatersrand.